The Pelasgians

The name Pelasgians (/pəˈlæzdʒiənz, -dʒənz, -ɡiənz/; Albanian: Pellazgët, Greek: Πελασγοί, Pelasgoí; singular: Πελασγός, Pelasgós) was used by some ancient Greek writers to refer to populations that were either the ancestors of the Ancient Greeks or preceded the Greeks in Greece, "a hold-all term for any ancient, primitive and presumably indigenous people in the Greek world".[1] In general, "Pelasgian" has come to mean more broadly all the indigenous inhabitants of the Aegean Sea region and their cultures before the advent of the Greek language.[2]

During the classical period, enclaves under that name survived in several locations of mainland Greece, Crete, and other regions of the Aegean. Populations identified as "Pelasgian" spoke a language or languages that at the time Greeks identified as "barbaric", even though some ancient writers described the Pelasgians as Greeks. A tradition also survived that large parts of Greece had once been Pelasgian before being Hellenized. These parts generally fell within the ethnic domain that, by the 5th century BC, was attributed to those speakers of ancient Greek who were identified as Ionians.

During the classical period, enclaves under that name survived in several locations of mainland Greece, Crete, and other regions of the Aegean. Populations identified as "Pelasgian" spoke a language or languages that at the time Greeks identified as "barbaric", even though some ancient writers described the Pelasgians as Greeks. A tradition also survived that large parts of Greece had once been Pelasgian before being Hellenized. These parts generally fell within the ethnic domain that, by the 5th century BC, was attributed to those speakers of ancient Greek who were identified as Ionians.

Origin

The Pelasgians are people who are wrapped in myth without a certain origin.

Territory

The Pelasgains had a far reach of the ancient world. The stretched from accross all the mediteranians, as far west as the Iberian and as far ease as Asia Minor.

As Fathers of Nations

One major theory utilizes the name "Pelasgian" to describe the inhabitants of the lands around the Aegean Sea before the arrival of proto-Greek speakers, as well as traditionally identified enclaves of descendants that still existed in classical Greece. The theory derives from the original concepts of the philologist Paul Kretschmer, whose views prevailed throughout the first half of the 20th century and are still given some credibility today.

Though Wilamowitz-Moellendorff wrote them off as mythical, the results of archaeological excavations at Çatalhöyük by James Mellaart and Fritz Schachermeyr led them to conclude that the Pelasgians had migrated from Asia Minor to the Aegean basin in the 4th millennium BC.[61] In this theory, a number of possible non-Indo-European linguistic and cultural features are attributed to the Pelasgians:

"There are, indeed, various names affirmed to designate the ante-Hellenic inhabitants of many parts of Greece — the Pelasgi, the Leleges, the Curetes, the Kaukones, the Aones, the Temmikes, the Hyantes, the Telchines, the Boeotian Thracians, the Teleboae, the Ephyri, the Phlegyae, &c. These are names belonging to legendary, not to historical Greece — extracted out of a variety of conflicting legends by the logographers and subsequent historians, who strung together out of them a supposed history of the past, at a time when the conditions of historical evidence were very little understood. That these names designated real nations may be true but here our knowledge ends."

The poet and mythologist Robert Graves asserts that certain elements of that mythology originate with the native Pelasgian people (namely the parts related to his concept of the White Goddess, an archetypical Earth Goddess) drawing additional support for his conclusion from his interpretations of other ancient literature: Irish, Welsh, Greek, Biblical, Gnostic, and medieval writings.[63]

Ibero-Caucasian[edit]Some Georgian scholars (including R. V. Gordeziani and M. G. Abdushelishvili) connect the Pelasgians with the Ibero-Caucasian peoples of the prehistoric Caucasus, known to the Greeks as Colchians and Iberians.[64]

Pelasgian as Indo-European[edit]Anatolian[edit]In western Anatolia, many toponyms with the "-ss-" infix derive from the adjectival suffix also seen in cuneiform Luwian and some Palaic; the classic example is Bronze Age Tarhuntassa (loosely, "City of the Storm God Tarhunta"), and later Parnassus may be related to the Hittite word parna- or "house". These elements have led to a second theory, that Pelasgian was to some degree an Anatolian language.

Thracian[edit]Vladimir I. Georgiev, a Bulgarian linguist, asserted that the Pelasgians were Indo-Europeans, with an Indo-European etymology of pelasgoi from pelagos, "sea" as the Sea People, the PRŚT of Egyptian inscriptions, and related them to the neighbouring Thracians. He proposed a soundshift model from Indo-European to Pelasgian.[65]

Greek[edit]Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, an English writer and intellectual, argued that the Pelasgians spoke Greek based on the fact that areas traditionally inhabited by the "Pelasgi" (i.e. Arcadia and Attica) only spoke Greek and that the few surviving Pelasgian words and inscriptions (i.e. Lamina Borgiana) betray Greek linguistic features.[66]

Albanian

See also: Origins of the Albanians § Obsolete theories and Albanian nationalismIn 1854, an Austrian diplomat and Albanian language specialist, Johann Georg von Hahn, identified the Pelasgian language with Ur-Albanian. This theory has been rejected by modern scholars.[67]

Undiscovered Indo-European[edit]Following Vladimir I. Georgiev,[68] who placed Pelasgian as an Indo-European language "between Albanian and Armenian",[69] Albert Joris Van Windekens (1915—1989) offered rules for an unattested hypothetical Indo-European Pelasgian language, selecting vocabulary for which there was no Greek etymology among the names of places, heroes, animals, plants, garments, artifacts, social organization.[70] His 1952 essay Le Pélasgique was critically received.[71]

Though Wilamowitz-Moellendorff wrote them off as mythical, the results of archaeological excavations at Çatalhöyük by James Mellaart and Fritz Schachermeyr led them to conclude that the Pelasgians had migrated from Asia Minor to the Aegean basin in the 4th millennium BC.[61] In this theory, a number of possible non-Indo-European linguistic and cultural features are attributed to the Pelasgians:

- Groups of apparently non-Indo-European loan words in the Greek language, borrowed in its prehistoric development.

- Non-Greek and possibly non-Indo-European roots for many Greek toponyms in the region, containing the consonantal strings "-nth-" (e.g., Corinth, Probalinthos, Zakynthos, Amarynthos), or its equivalent "-ns-" (e.g., Tiryns); "-tt-", e.g., in the peninsula of Attica, Mounts Hymettus and Brilettus/Brilessus, Lycabettus Hill, the deme of Gargettus, etc.; or its equivalent "-ss-": Larissa, Mount Parnassus, the river names Kephissos and Ilissos, the Cretan cities of Amnis(s)os and Tylissos etc. These strings also appear in other non-Greek, presumably substratally inherited nouns such as asáminthos (bathtub), ápsinthos (absinth), terébinthos (terebinth), etc. Other placenames with no apparent Indo-European etymology include Athēnai (Athens), Mykēnai (Mycene), Messēnē, Kyllēnē(Cyllene), Cyrene, Mytilene, etc. (note the common -ēnai/ēnē ending); also Thebes, Delphi, Lindos, Rhamnus, and others.

- Certain mythological stories or deities that seem to have no parallels in the mythologies of other Indo-European peoples (e. g., the Olympians Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, and Aphrodite, whose origins seem Anatolian or Levantine).

- Non-Greek inscriptions throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Lemnos stele.

"There are, indeed, various names affirmed to designate the ante-Hellenic inhabitants of many parts of Greece — the Pelasgi, the Leleges, the Curetes, the Kaukones, the Aones, the Temmikes, the Hyantes, the Telchines, the Boeotian Thracians, the Teleboae, the Ephyri, the Phlegyae, &c. These are names belonging to legendary, not to historical Greece — extracted out of a variety of conflicting legends by the logographers and subsequent historians, who strung together out of them a supposed history of the past, at a time when the conditions of historical evidence were very little understood. That these names designated real nations may be true but here our knowledge ends."

The poet and mythologist Robert Graves asserts that certain elements of that mythology originate with the native Pelasgian people (namely the parts related to his concept of the White Goddess, an archetypical Earth Goddess) drawing additional support for his conclusion from his interpretations of other ancient literature: Irish, Welsh, Greek, Biblical, Gnostic, and medieval writings.[63]

Ibero-Caucasian[edit]Some Georgian scholars (including R. V. Gordeziani and M. G. Abdushelishvili) connect the Pelasgians with the Ibero-Caucasian peoples of the prehistoric Caucasus, known to the Greeks as Colchians and Iberians.[64]

Pelasgian as Indo-European[edit]Anatolian[edit]In western Anatolia, many toponyms with the "-ss-" infix derive from the adjectival suffix also seen in cuneiform Luwian and some Palaic; the classic example is Bronze Age Tarhuntassa (loosely, "City of the Storm God Tarhunta"), and later Parnassus may be related to the Hittite word parna- or "house". These elements have led to a second theory, that Pelasgian was to some degree an Anatolian language.

Thracian[edit]Vladimir I. Georgiev, a Bulgarian linguist, asserted that the Pelasgians were Indo-Europeans, with an Indo-European etymology of pelasgoi from pelagos, "sea" as the Sea People, the PRŚT of Egyptian inscriptions, and related them to the neighbouring Thracians. He proposed a soundshift model from Indo-European to Pelasgian.[65]

Greek[edit]Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, an English writer and intellectual, argued that the Pelasgians spoke Greek based on the fact that areas traditionally inhabited by the "Pelasgi" (i.e. Arcadia and Attica) only spoke Greek and that the few surviving Pelasgian words and inscriptions (i.e. Lamina Borgiana) betray Greek linguistic features.[66]

Albanian

See also: Origins of the Albanians § Obsolete theories and Albanian nationalismIn 1854, an Austrian diplomat and Albanian language specialist, Johann Georg von Hahn, identified the Pelasgian language with Ur-Albanian. This theory has been rejected by modern scholars.[67]

Undiscovered Indo-European[edit]Following Vladimir I. Georgiev,[68] who placed Pelasgian as an Indo-European language "between Albanian and Armenian",[69] Albert Joris Van Windekens (1915—1989) offered rules for an unattested hypothetical Indo-European Pelasgian language, selecting vocabulary for which there was no Greek etymology among the names of places, heroes, animals, plants, garments, artifacts, social organization.[70] His 1952 essay Le Pélasgique was critically received.[71]

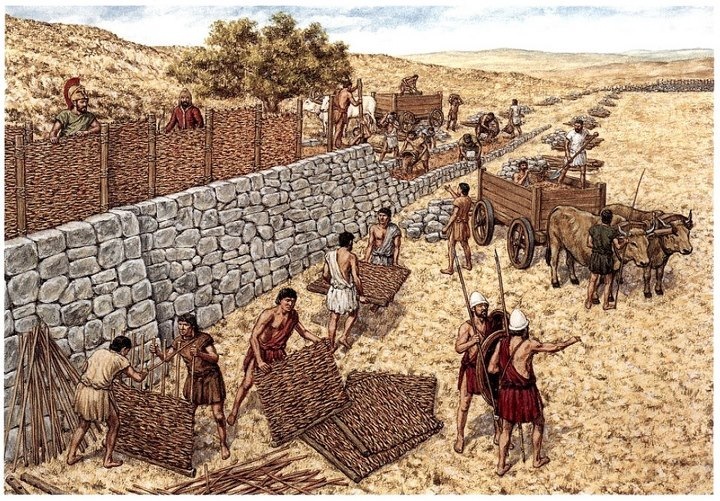

As builders

As priests

In the Trojan War

In the Bible

Peleg (Hebrew: פּלג, Pẹleḡ; Greek: Φάλεγ, Phaleg[1]; "Name means::division") (Born::Tammuz 1757 AM-Died::Tammuz 1996 AM) is the first named son of son of::Eber. He had at least one known brother, brother of::Joktan. When he was age of parenthood::30 years old, he had a son named father of::Reu. He lived for another 209 years and had other sons and daughters.[2] His total life span was thus life span::239 years, slightly more than half that of his father and the shortest life span to date in his line.

Some writers, such as Perry Edward Powell[5] and Arthur C. Custance[6] associate the Pelasgi or Pelasgians with Peleg; these were Indo-Europeans who claimed Pelasgus as their first king.[7][8] Greek Orthodox tradition also affirms this connection. Strabo says in his Geography, "... the Pelasgi were by the Attic people called 'Pelargi,' the compilers add, because they were wanderers and, like birds, resorted to those places wither chance led them."[9] Gamkrelidze and Ivanov claim that the Pelasgians settled the Peloponnesian peninsula "even before the arrival of the Greeks [Hellenes] proper."[10]Elsewhere Strabo cites Greek writers who claimed that the Pelasgians came from Thessaly,[11] and there a people whom Strabo calls Pelagonians are found,[12] so there may be some merit to this assertion. The Pelasgians are said to have "spread throughout the whole of Greece" in ancient times,[13]and when the Danaans came from Egypt, they were also called by that name.[14] The apparently peaceful reception of the Danaans in Greece may well be explained, if those inhabitants of Greece before the arrival of Dan were also Hebrews. The Pelasgians were a sea-faring people who sailed theMediterranean and were well known as traders. John Denison Baldwin suggests that acknowledgment of the Pelasgians was recorded in Sanskrit which mentions the Palangshu of Asia Minor (Placia and Mysia).[15] They also occupied a territory north of Greece between two rivers, one of which was called the Hebrus River, bearing a name reminiscent of and most likely named after their ancestor, Eber (Genesis 10:25 ).[16] Eventually they were pushed further south by the Thracians and they merged with the Mycenaean Greeks. They seem to be the only people ascribed to him.

Some writers, such as Perry Edward Powell[5] and Arthur C. Custance[6] associate the Pelasgi or Pelasgians with Peleg; these were Indo-Europeans who claimed Pelasgus as their first king.[7][8] Greek Orthodox tradition also affirms this connection. Strabo says in his Geography, "... the Pelasgi were by the Attic people called 'Pelargi,' the compilers add, because they were wanderers and, like birds, resorted to those places wither chance led them."[9] Gamkrelidze and Ivanov claim that the Pelasgians settled the Peloponnesian peninsula "even before the arrival of the Greeks [Hellenes] proper."[10]Elsewhere Strabo cites Greek writers who claimed that the Pelasgians came from Thessaly,[11] and there a people whom Strabo calls Pelagonians are found,[12] so there may be some merit to this assertion. The Pelasgians are said to have "spread throughout the whole of Greece" in ancient times,[13]and when the Danaans came from Egypt, they were also called by that name.[14] The apparently peaceful reception of the Danaans in Greece may well be explained, if those inhabitants of Greece before the arrival of Dan were also Hebrews. The Pelasgians were a sea-faring people who sailed theMediterranean and were well known as traders. John Denison Baldwin suggests that acknowledgment of the Pelasgians was recorded in Sanskrit which mentions the Palangshu of Asia Minor (Placia and Mysia).[15] They also occupied a territory north of Greece between two rivers, one of which was called the Hebrus River, bearing a name reminiscent of and most likely named after their ancestor, Eber (Genesis 10:25 ).[16] Eventually they were pushed further south by the Thracians and they merged with the Mycenaean Greeks. They seem to be the only people ascribed to him.

Eber were born two sons: the first was called Peleg, because it was in his time that the earth was divided, and his brother was called Joktan. (Genesis 10:25)

Link to Albanian

Also see

- Illyrians

- Epiriottes

- Dardanians

- Macedonians

- Pelasgian Creation Myth

References

The Mediterranean Race