Albania in the Balkan Wars

Independent Albania was proclaimed on 28 November 1912. This chapter of Albanian history was shrouded in controversy and conflict as the larger part of the self-proclaimed region had found itself controlled by the Balkan League states: Serbia,Montenegro and Greece from the time of the declaration until the period of recognition when Albania relinquished many of the lands originally included in the declared state. Since the proclamation of the state in November 1912, the Provisional Government of Albania asserted its control over a small part of central Albania including the important cities of Vlorë and Berat.

Provisional Government of 1912

1912 was to be an eventful year in Rumelia. From August, the Ottoman Government recognized the autonomy of Albania.[1][2] In October 1912, the Balkan states, following their own national aspirations[3][4] jointly attacked the Ottoman Empire and during the next few months partitioned nearly all of Rumelia, the Ottoman territories in Europe, including those inhabited by the Albanians.[5] In November, with the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the Albanians rose up and declared the creation of an independent Albania, which included all of what is now Albania and Kosovo.[6]

Campaigns by Balkan League members in Ottoman Albania

Serbian campaign

Main articles: Serbia in the Balkan Wars and Drač County

The Serb army first entered Ottoman territory inhabited by ethnic Albanians in October 1912 as part of its campaign in the then-ongoing First Balkan War.[7] The Kingdom of Serbia occupied most of the Albanian-inhabited lands including Albania's Adriatic coast. Serbian Gen. Božidar Janković was the Commander of the Serbian Third Army during the military campaign in Albania. The Serbian army met with strong Albanian guerrilla resistance, led by Isa Boletini, Azem Galica and other military leaders. During the Serbian occupation, Gen. Jankovic forced notables and local tribal leaders to sign a declaration of gratitude to King Petar I Karađorđević for their "liberation by the Serbian army".[8]

The army of the Kingdom of Serbia captured Durrës on 29 November 1912 without any resistance. Right after their arrival in Durrës, on 29 November 1912, the Kingdom of Serbia established Drač County, its district offices and appointed the governor of the county, mayor of the city and commander of the military garrison.[9]

During the occupation, the Serbian army committed numerous crimes against the Albanian population "with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of these regions."[5] The Serbian government denied reports of war crimes.[8]

Following the signing of the Treaty of London in May 1913 which awarded new lands to Serbia, including most of the former Vilayet of Kosovo, the Serbian government agreed to withdraw its troops from outside of its newly expanded territory. This allowed an Albanian state to exist peacefully. The final withdrawal of Serb personnel from Albania was in October 1913.

Montenegrin campaign

Main article: Siege of Scutari (1912–1913)

Shkodër and its surrounding had long been desired by Montenegro, although its inhabitants were overwhelmingly ethnic Albanians. The Siege of Scutari took place on 23 April 1913 between the allied forces of Montenegro and Serbia against the forces of the Ottoman Empire and the Provisional Government of Albania.

Montenegro took Shkodër on 23 April 1913, but when the war was over the Great Powers didn't give the city to the Kingdom of Montenegro, which was compelled to evacuate it in May 1913, in accordance with the London Conference of Ambassadors. The army's withdrawal was hastened by a small naval flotilla of British and Italian gunboats that moved up the Bojana River and across the Adriatic coastline.[10]

Greek campaign

Main article: Greece in the Balkan Wars

Caricature shows Albania defending itself from neighboring countries. Montenegro is represented as a monkey, Greece as a leopard and Serbia as a snake. Text in Albanian: "Flee from me! Bloodsucker Beasts!"

The Greek Army controlled territory that would be later incorporated into the Alba

nian state before the declaration of Albanian Independence in Vlorë. On 18 November 1912, after a successful uprising and 10 days prior to the Albanian Declaration of Independence, local Maj. Spyros Spyromilios expelled the Ottomans from the Himara region.[11] The Greek Navy also shelled the city of Vlora on 3 December 1912.[12][13] The Greek Army didn't capture Vlore, which was of great interest to Italy.[14]

Greek forces were stationed in what would become southern Albania until March 1914. After the Great Powers agreed on the terms of the Protocol of Florence in December 1913, Greece was forced to retreat from the towns of Korçë, Gjirokastër and Sarandë and the surrounding territories.[15]

Massacre of the Albanians

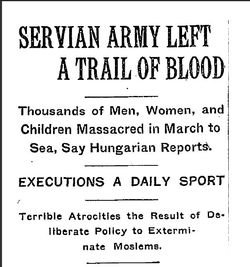

The New York Times, 31.December 1912.

The New York Times, 31.December 1912.

A series of massacres of Albanians in the Balkan Wars were committed by the Serbian and Montenegrin Army and paramilitaries, according to international reports.[17]

Prior to the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the Albanian nation was fighting for a national state. At the end of 1912, the Porte recognised the autonomy of Albanian vilayet.

The Balkan League (comprising:Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria) jointly attacked the Ottoman Empire and during the next few months partitioned all Ottoman territory inhabited by Albanians.[17] The Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Greece occupied most of the land of what is today Albania and other lands inhabited by Albanians on the Adriatic coast. Montenegro occupied a part of today's northern Albania around Shkodër.

During the First Balkan War of 1912-13, Serbia and Montenegro - after expelling the Ottoman forces in present-day Albania and Kosovo - committed numerous war crimes against the Albanian population, which were reported by the European, American and Serbian opposition press.[18] In order to investigate the crimes, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace formed a special commission, which was sent to the Balkans in 1913. Summing the situation in Albanian areas, Commission concludes:

Houses and whole villages reduced to ashes, unarmed and innocent populations massacred en masse, incredible acts of violence, pillage and brutality of every kind — such were the means which were employed and are still being employed by the Serbo-Montenegrin soldiery, with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians.[17]— Report of the International Commission on the Balkan Wars

The goal of the forced expulsions and massacres of ethnic Albanians was a statistic manipulation before the London Ambassadors Conference which was to decide on the new Balkan borders.[18][19][20] The number of victims in the Vilayet of Kosovo under Serbian control in the first few months was estimated at about 25,000 people.[18][20][21] Highest estimated number of total casualties during the occupation in all the Albanian areas under Serbian control was about 120,000 Albanians of both sexes and all ages.[22]

Even one Serb Social Democrat who had served in the army previously commented on the disgust he had for the crimes his own people had committed against the Albanians, describing in great detail heaps of dead, headless Albanians in the centers of a string of burnt towns near Kumanovo and Skopje:

...the horrors actually began as soon as we crossed the old frontier. By five p.m. we were approaching Kumanovo. The sun had set, it was starting to get dark. But the darker the sky became, the more brightly the fearful illumination of the fires stood out against it. Burning was going on all around us. Entire Albanian villages had been turned into pillars of fire... In all its fiery monotony this picture was repeated the whole way to Skopje... For two days before my arrival in Skopje the inhabitants had woken up in the morning to the sight, under the principal bridge over the Vardar- that is, in the very centre of the town- of heaps of Albanian corpses with severed heads. Some said that these were local Albanians, killed by the komitadjis [cjetniks], others that the corpses were brought down to the bridge by the waters of the Vardar. What was clear was that these headless men had not been killed in battle.[23]

Prishtina

When villagers heard about the Serbian massacres of Albanians in the nearby villages, some houses took the desperate measure of raising white flag to protect themselves. In the cases the white flag was ignored during the attack of Serbian army on Prishtina in October 1912, the Albanians (led by Turkish officers) abused the white flag, and attacked Serbian soldiers.[21] The Serbian army subsequently used this as an excuse for the brutal retaliation of the civilians. Reports said that immediately upon entering the city, the Serbian army began hunting the Albanians and created a bloodshed by decimating the Albanian population of Prishtina.[18]

The number of Albanians of Prishtina killed in the early days of the Serbian government is estimated at 5,000.[21][24]

Ferizaj

Ferizaj fell to Serbia, the local Albanian population gave a determined resistance. According to some reports, the fight for the city lasted three days.[18] After the fall of the city to the Serbian Army, the Serbian commander ordered the population to go back home and to surrender the weapons. When the survivors returned, between 300-400 people were massacred.[18] Then followed the destruction of Albanian-populated villages around Ferizaj.[25]

Gjakova

Gjakova was mentioned among the cities that suffered at the hands of the Serbian-Montenegrin army. The New York Times reported that people on the gallows hung on both sides of the road, and that the way to Yakova became a "gallows alley."[24] In the region of Yakova, the Montenegrin police-military formation Kraljevski žandarmerijski kor, known as krilaši, committed many abuses and violence against the Albanian population.[26]

In Gjakova, Serbian priests carried out a violent conversion of Albanian Catholics to Serbian Orthodoxy.[27] Vienna Neue Freie Presse (20 March 1913) reported that Orthodox priests with the help of military force converted 300 Gjakova Catholics to the Orthodox faith, and that Franciscan Pater Angelus, who refused to renounce his faith, was tortured and then killed with bayonets. The History Institute in Pristina has claimed that Montenegro converted over 1,700 Albanian Catholics to the Serbian Orthodox faith in the area of Gjakova in March 1913.[28]

Prizren

After the Serbian army achieved control over the city of Prizren, it imposed repressive measures against the Albanian civilian population. Serbian detachments broke into houses, plundered, committed acts of violence, and killed indiscriminately.[18] Around 400 people were "eradicated" in the first days of the Serbian military administration.[18] During those days bodies were lying everywhere on the streets. According to witnesses, during those days around Prizren lay about 1,500 corpses of Albanians.[21] Foreign reporters were not allowed to go to Prizren.[21] After the operations of the Serbian military and paramilitary units, Prizren became one of the most devastated cities of the Kosovo vilayet and people called it "the Kingdom of Death".[21] Eventually, General Božidar Janković forced surviving Albanian leaders of Prizren to sign a statement of gratitude to the Serbian king Peter I Karađorđević for their liberation.[21] It is estimated that 5,000 Albanians was massacred in the area of Prizren.[21] British traveller Edith Durham and a British military attaché were supposed to visit Prizren in October 1912, however the trip was prevented by the authorities. Durham stated " I asked wounded Montengrins [Soldiers] why I was not allowed to go and they laughed and said 'We have not left a nose on an Albanian up there!' Not a pretty sight for a British officer." Eventually Durham visited a northern Albanian outpost in Kosovo where she met captured Ottoman soldiers whose upper lips and noses had been cut off.[29]

Luma

When General Janković saw that the Albanians of Luma would not allow Serbian forces to continue the advance to the Adriatic Sea, he ordered the troops to continue their brutality.[18] The Serbian army massacred an entire population of men, women and children, not sparing anyone, and burned 27 villages in the area of Luma.[21] Reports spoke of the atrocities by the Serbian army, including the burning of women and children bound to stacks of hay, within the sight of their fathers.[18] Subsequently, about 400 men from Luma surrendered to Serbian authorities, but were taken to Prizren, where they were murdered.[18] The Daily Telegraph wrote that "all the horrors of history have been outdone by the atrocious conduct of the troops of General Jankovic".[18]

The second Luma massacre was committed the following year (1913). After the London Ambassador Conference decided that Luma should be within the Albanian state, the Serbian army initially refused to withdraw. Albanians raised a great rebellion in September 1913, after which Luma once again suffered harsh retaliation from the Serbian army. A report of the International Commission cited a letter of a Serbian soldier, who described the punitive expedition against the rebel Albanians:[17]

"My dear Friend, I have no time to write to you at length, but I can tell you that appalling things are going on here. I am terrified by them, and constantly ask myself how men can be so barbarous as to commit such cruelties. It is horrible. I dare not tell you more, but I may say that Luma (an Albanian region along the river of the same name), no longer exists. There is nothing but corpses, dust and ashes. There are villages of 100, 150, 200 houses, where there is no longer a single man, literally not one. We collect them in bodies of forty to fifty, and then we pierce them with our bayonets to the last man. Pillage is going on everywhere. The officers told the soldiers to go to Prizren and sell the things they had stolen."

Italian daily newspaper Corriere delle Puglie wrote in December 1913 about official report that was sent to the Great Powers with details of the slaughter of Albanians in Luma and Debar, executed after the proclamation of the amnesty by Serbian authorities. The report listed the names of people killed by Serbian units in addition to the causes of death: by burning, slaughtering, bayonets, etc. The report also provided a detailed list of the burned and looted villages in the area of Luma and Has.[30]

Leo Trotsky's article

Leo Trotsky, one of the leading figures of the Russian revolution, was sent as a journalist to cover Balkan Wars in Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania. In his report sent to Kiev newspaper Kievskaya Misl he writes about many "atrocities committed against the Albanians of Macedonia and Kosovo in the wake of the Serb invasion of October 1912".[31] Among other instances he tells a shocking case of drunken Serbian soldiers torturing two young Albanians. "Four soldiers held their bayonets in readiness and in their midst stood two young Albanians with their white felt caps on their heads. A drunken sergeant – a komitadji – was holding a kama (a Macedonian dagger) in one hand and a bottle of cognac in the other. The sergeant ordered: ‘On your knees!’ (The petrified Albanians fell to their knees. ‘To your feet!’ They stood up. This was repeated several times. Then the sergeant, threatening and cursing, put the dagger to the necks and chests of his victims and forced them to drink some cognac, and then… he kissed them...", shows an excerpt from the report.[31]

Mark Mazower

Mark Mazower, who has written extensively on Balkan history, in his work The Balkans, From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day (for which he won the Wolfson History Prize which "promotes and encourages standards of excellence in the writing of history for the general public") claims:

In the former Ottoman districts of Kosovo and Monastir, in particular, the conquering Serb army killed perhaps thousands of civilians. Despite some Serb officer's careless talk of “exterminating” the Albanian population, this was killing prompted more by revenge than genocide.— Mark Mazower[32]

Henrik August Angel, a Norwegian military officer and writer who personally followed the trail of the Ottoman army and army of Kingdom of Serbia, in his work[33] described demonization of Serbs in texts published in newspapers on English, and especially on German in newspapers from Germany and Austria-Hungary, as "shameful injustice".[34]

Epilogue

“We have carried out the attempted premeditated murder of an entire nation. We were caught in that criminal act and have been obstructed. Now we have to suffer the punishment.... In the Balkan Wars, Serbia not only doubled its territory, but also its external enemies.[35]” — Dimitrije Tucović

As a result of the Treaty of London in 1913 which designated the former Ottoman lands to Serbia, Montenegro and Greece (namely, the large part of the Vilayet of Kosovo being awarded to Serbia), an independent Albania was recognised. As such, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro agreed to withdraw from the territory of the new Principality of Albania. The principality however included only about half of the territory populated by ethnic Albanians and a large number of Albanians remained in neighboring countries.[36]

These events have greatly contributed to the growth of the Serbian-Albanian conflict.[37]

Prior to the outbreak of the First Balkan War, the Albanian nation was fighting for a national state. At the end of 1912, the Porte recognised the autonomy of Albanian vilayet.

The Balkan League (comprising:Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria) jointly attacked the Ottoman Empire and during the next few months partitioned all Ottoman territory inhabited by Albanians.[17] The Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Greece occupied most of the land of what is today Albania and other lands inhabited by Albanians on the Adriatic coast. Montenegro occupied a part of today's northern Albania around Shkodër.

During the First Balkan War of 1912-13, Serbia and Montenegro - after expelling the Ottoman forces in present-day Albania and Kosovo - committed numerous war crimes against the Albanian population, which were reported by the European, American and Serbian opposition press.[18] In order to investigate the crimes, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace formed a special commission, which was sent to the Balkans in 1913. Summing the situation in Albanian areas, Commission concludes:

Houses and whole villages reduced to ashes, unarmed and innocent populations massacred en masse, incredible acts of violence, pillage and brutality of every kind — such were the means which were employed and are still being employed by the Serbo-Montenegrin soldiery, with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians.[17]— Report of the International Commission on the Balkan Wars

The goal of the forced expulsions and massacres of ethnic Albanians was a statistic manipulation before the London Ambassadors Conference which was to decide on the new Balkan borders.[18][19][20] The number of victims in the Vilayet of Kosovo under Serbian control in the first few months was estimated at about 25,000 people.[18][20][21] Highest estimated number of total casualties during the occupation in all the Albanian areas under Serbian control was about 120,000 Albanians of both sexes and all ages.[22]

Even one Serb Social Democrat who had served in the army previously commented on the disgust he had for the crimes his own people had committed against the Albanians, describing in great detail heaps of dead, headless Albanians in the centers of a string of burnt towns near Kumanovo and Skopje:

...the horrors actually began as soon as we crossed the old frontier. By five p.m. we were approaching Kumanovo. The sun had set, it was starting to get dark. But the darker the sky became, the more brightly the fearful illumination of the fires stood out against it. Burning was going on all around us. Entire Albanian villages had been turned into pillars of fire... In all its fiery monotony this picture was repeated the whole way to Skopje... For two days before my arrival in Skopje the inhabitants had woken up in the morning to the sight, under the principal bridge over the Vardar- that is, in the very centre of the town- of heaps of Albanian corpses with severed heads. Some said that these were local Albanians, killed by the komitadjis [cjetniks], others that the corpses were brought down to the bridge by the waters of the Vardar. What was clear was that these headless men had not been killed in battle.[23]

Prishtina

When villagers heard about the Serbian massacres of Albanians in the nearby villages, some houses took the desperate measure of raising white flag to protect themselves. In the cases the white flag was ignored during the attack of Serbian army on Prishtina in October 1912, the Albanians (led by Turkish officers) abused the white flag, and attacked Serbian soldiers.[21] The Serbian army subsequently used this as an excuse for the brutal retaliation of the civilians. Reports said that immediately upon entering the city, the Serbian army began hunting the Albanians and created a bloodshed by decimating the Albanian population of Prishtina.[18]

The number of Albanians of Prishtina killed in the early days of the Serbian government is estimated at 5,000.[21][24]

Ferizaj

Ferizaj fell to Serbia, the local Albanian population gave a determined resistance. According to some reports, the fight for the city lasted three days.[18] After the fall of the city to the Serbian Army, the Serbian commander ordered the population to go back home and to surrender the weapons. When the survivors returned, between 300-400 people were massacred.[18] Then followed the destruction of Albanian-populated villages around Ferizaj.[25]

Gjakova

Gjakova was mentioned among the cities that suffered at the hands of the Serbian-Montenegrin army. The New York Times reported that people on the gallows hung on both sides of the road, and that the way to Yakova became a "gallows alley."[24] In the region of Yakova, the Montenegrin police-military formation Kraljevski žandarmerijski kor, known as krilaši, committed many abuses and violence against the Albanian population.[26]

In Gjakova, Serbian priests carried out a violent conversion of Albanian Catholics to Serbian Orthodoxy.[27] Vienna Neue Freie Presse (20 March 1913) reported that Orthodox priests with the help of military force converted 300 Gjakova Catholics to the Orthodox faith, and that Franciscan Pater Angelus, who refused to renounce his faith, was tortured and then killed with bayonets. The History Institute in Pristina has claimed that Montenegro converted over 1,700 Albanian Catholics to the Serbian Orthodox faith in the area of Gjakova in March 1913.[28]

Prizren

After the Serbian army achieved control over the city of Prizren, it imposed repressive measures against the Albanian civilian population. Serbian detachments broke into houses, plundered, committed acts of violence, and killed indiscriminately.[18] Around 400 people were "eradicated" in the first days of the Serbian military administration.[18] During those days bodies were lying everywhere on the streets. According to witnesses, during those days around Prizren lay about 1,500 corpses of Albanians.[21] Foreign reporters were not allowed to go to Prizren.[21] After the operations of the Serbian military and paramilitary units, Prizren became one of the most devastated cities of the Kosovo vilayet and people called it "the Kingdom of Death".[21] Eventually, General Božidar Janković forced surviving Albanian leaders of Prizren to sign a statement of gratitude to the Serbian king Peter I Karađorđević for their liberation.[21] It is estimated that 5,000 Albanians was massacred in the area of Prizren.[21] British traveller Edith Durham and a British military attaché were supposed to visit Prizren in October 1912, however the trip was prevented by the authorities. Durham stated " I asked wounded Montengrins [Soldiers] why I was not allowed to go and they laughed and said 'We have not left a nose on an Albanian up there!' Not a pretty sight for a British officer." Eventually Durham visited a northern Albanian outpost in Kosovo where she met captured Ottoman soldiers whose upper lips and noses had been cut off.[29]

Luma

When General Janković saw that the Albanians of Luma would not allow Serbian forces to continue the advance to the Adriatic Sea, he ordered the troops to continue their brutality.[18] The Serbian army massacred an entire population of men, women and children, not sparing anyone, and burned 27 villages in the area of Luma.[21] Reports spoke of the atrocities by the Serbian army, including the burning of women and children bound to stacks of hay, within the sight of their fathers.[18] Subsequently, about 400 men from Luma surrendered to Serbian authorities, but were taken to Prizren, where they were murdered.[18] The Daily Telegraph wrote that "all the horrors of history have been outdone by the atrocious conduct of the troops of General Jankovic".[18]

The second Luma massacre was committed the following year (1913). After the London Ambassador Conference decided that Luma should be within the Albanian state, the Serbian army initially refused to withdraw. Albanians raised a great rebellion in September 1913, after which Luma once again suffered harsh retaliation from the Serbian army. A report of the International Commission cited a letter of a Serbian soldier, who described the punitive expedition against the rebel Albanians:[17]

"My dear Friend, I have no time to write to you at length, but I can tell you that appalling things are going on here. I am terrified by them, and constantly ask myself how men can be so barbarous as to commit such cruelties. It is horrible. I dare not tell you more, but I may say that Luma (an Albanian region along the river of the same name), no longer exists. There is nothing but corpses, dust and ashes. There are villages of 100, 150, 200 houses, where there is no longer a single man, literally not one. We collect them in bodies of forty to fifty, and then we pierce them with our bayonets to the last man. Pillage is going on everywhere. The officers told the soldiers to go to Prizren and sell the things they had stolen."

Italian daily newspaper Corriere delle Puglie wrote in December 1913 about official report that was sent to the Great Powers with details of the slaughter of Albanians in Luma and Debar, executed after the proclamation of the amnesty by Serbian authorities. The report listed the names of people killed by Serbian units in addition to the causes of death: by burning, slaughtering, bayonets, etc. The report also provided a detailed list of the burned and looted villages in the area of Luma and Has.[30]

Leo Trotsky's article

Leo Trotsky, one of the leading figures of the Russian revolution, was sent as a journalist to cover Balkan Wars in Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania. In his report sent to Kiev newspaper Kievskaya Misl he writes about many "atrocities committed against the Albanians of Macedonia and Kosovo in the wake of the Serb invasion of October 1912".[31] Among other instances he tells a shocking case of drunken Serbian soldiers torturing two young Albanians. "Four soldiers held their bayonets in readiness and in their midst stood two young Albanians with their white felt caps on their heads. A drunken sergeant – a komitadji – was holding a kama (a Macedonian dagger) in one hand and a bottle of cognac in the other. The sergeant ordered: ‘On your knees!’ (The petrified Albanians fell to their knees. ‘To your feet!’ They stood up. This was repeated several times. Then the sergeant, threatening and cursing, put the dagger to the necks and chests of his victims and forced them to drink some cognac, and then… he kissed them...", shows an excerpt from the report.[31]

Mark Mazower

Mark Mazower, who has written extensively on Balkan history, in his work The Balkans, From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day (for which he won the Wolfson History Prize which "promotes and encourages standards of excellence in the writing of history for the general public") claims:

In the former Ottoman districts of Kosovo and Monastir, in particular, the conquering Serb army killed perhaps thousands of civilians. Despite some Serb officer's careless talk of “exterminating” the Albanian population, this was killing prompted more by revenge than genocide.— Mark Mazower[32]

Henrik August Angel, a Norwegian military officer and writer who personally followed the trail of the Ottoman army and army of Kingdom of Serbia, in his work[33] described demonization of Serbs in texts published in newspapers on English, and especially on German in newspapers from Germany and Austria-Hungary, as "shameful injustice".[34]

Epilogue

“We have carried out the attempted premeditated murder of an entire nation. We were caught in that criminal act and have been obstructed. Now we have to suffer the punishment.... In the Balkan Wars, Serbia not only doubled its territory, but also its external enemies.[35]” — Dimitrije Tucović

As a result of the Treaty of London in 1913 which designated the former Ottoman lands to Serbia, Montenegro and Greece (namely, the large part of the Vilayet of Kosovo being awarded to Serbia), an independent Albania was recognised. As such, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro agreed to withdraw from the territory of the new Principality of Albania. The principality however included only about half of the territory populated by ethnic Albanians and a large number of Albanians remained in neighboring countries.[36]

These events have greatly contributed to the growth of the Serbian-Albanian conflict.[37]

Aftermath

Under strong international pressure, Albania's Balkan neighbors were forced to withdraw from the territory of the internationally recognized state of Albania in 1913. The new Principality of Albania included only about half of the ethnic Albanian population, while a large number of Albanians remained in neighboring countries.[16]

Also see

- Albanophobia

- Albanian Principality

References

- Balkan studies, Volume 25 Author Hidryma Meletōn Chersonēsou tou Haimou (Thessalonikē, Greece) Publisher The Institute, 1984 p.385

- The case for Kosova: passage to independence Author Anna Di Lellio Publisher Anthem Press, 2006 ISBN 1-84331-229-8, ISBN 978-1-84331-229-1 p.55

- Balkan studies, Volume 25 Author Hidryma Meletōn Chersonēsou tou Haimou (Thessalonikē, Greece) Publisher The Institute, 1984 p.387

- The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927 Author William Miller Edition revised Publisher Routledge, 1966 ISBN 0-7146-1974-4, ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3 p.498

- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War (1914)

- Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia at peace and at war: selected writings, 1983 – 2007, by Sabrina P. Ramet

- Borislav Ratković, Mitar Đurišić, Savo Skoko, Srbija i Crna Gora u Balkanskim ratovima 1912–1913, Belgrade: BIGZ, 1972, pages 50–62.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Leo Freundlich: Albania's Golgotha

- Popović, Bogdan; Jovan Skerlić (1924). Srpski književni glasnik, Volume 11. p. 275. Retrieved 6 August 2011. 16. novembra odred je stigao u Drač gde je oduševljeno dočekan od hrišćanskog stanovništva. Odmah su postavljene naše policijske vlasti (načelstvo okruga dračkog, upravnik varoši, predsednik opštine i načelnik vojne stanice) i potom je bilo preduzeto utvrđivanje Drača... [transl.: 'On 16 November (i.e. Gregorian 29 November) the army units arrived in Durres, where they were welcomed warmly by the Christian population. They immediately began to organize our police authorities (the county of Durres, a city major, a president of the town and commander of the military station) and then set up further fortification of Durres.']

- Edith Durham, The Struggle for Scutari (Turk, Slav, and Albanian), (Edward Arnold, 1914)

- Kondis Basil. Greece and Albania, 1908–1914. Institute for Balkan Studies, 1976, p. 93.

- The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: prelude to the First World War, by Richard C. Hall

- The Albanians: a modern history, by Miranda Vickers (Page 69)

- Koliopoulos, John S.; Veremis, Thanos M. (2009). Modern Greece: A History Since 1821. Malden, Massachusetts: John Wiley and Sons. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4051-8681-0.

- The Albanians: a modern history, by Miranda Vickers (Page 80)

- The Conference of London 1913. Robert Elsie.

- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War (1914)

- Leo Freundlich: Albania's Golgotha

- Otpor okupaciji i modernizaciji

- Justice, Intervention and Force in International Relations, by Kimberly A. Hudson

- Archbishop Lazër Mjeda: Report on the Serb Invasion of Kosova and Macedonia

- Kosta Novaković, Srbizacija i kolonizacija Kosova

- Quoted in Trotsky, op, cit., pp 267. Cited in Glenny's Balkans, where quote here is copied from, page 234

- The New York Times, 31. December 1912.

- Leo Trotsky: Behind the Curtains of the Balkan Wars

- Krilaši, Istorijski leksikon Crne Gore, Daily Press, Podgorica, 2006.

- Zef Mirdita, Albanci u svjetlosti vanjske politike Srbije

- EXPULSIONS OF ALBANIANS AND COLONISATION OF KOSOVA II (The Institute of History, Prishtina)

- Noel Malcolm (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: papermac. p. 253. ISBN 9780330412247.

- Dole in Dibra: Official Report Submitted to the Great Powers

- Robert Elsie, Leo Trotsky: Behind the Curtains of the Balkan Wars

- Mazower, Mark (2001) [2000]. "Building the nation-state.". The Balkans, From the End of Byzantium to the Present Day. Great Britain: Phoenix Press.ISBN 978-1-84212-544-1.

- Henrik August, Angel (1995), Kada se jedan mali narod bori za život: Srpske vojničke priče, Haka, ISBN 978-86-81635-01-8

- Vlahović, Dragan (December 25, 2010). "Istorija — mit i zablude" [History — myth and misconceptions]. Politika (in Serbian) (Belgrade: Politika Newspapers and Magazines). Igrom slučaja.... prejahao poprište i sopstvenim nogama išao tragom turske i srpske vojske... Srbima naneta sramotna nepravda... sanjao dopisnik iz Budimpešte

- T. Gallagher, The Balkans in the New Millennium: In the Shadow of War and Peace, Routledge, 2006. ISBN 0-415-34940-0

- Robert Elsie, The Conference of London 1913

- Dimitrije Tucović: Serbien und Albanien: ein kritischer Beitrag zur Unterdrückungspolitik der serbischen Bourgeoisie