My of creation

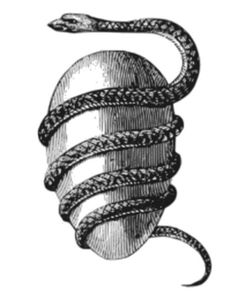

Mithras borned from the cosmic egg

Mithras borned from the cosmic egg

The Greek Myths (1955) is a mythography, a compendium of Greek mythology, with comments and analyses, by the poet and writer Robert Graves, normally published in two volumes, though there are abridged editions that present the myths only.

Each myth is presented in the voice of a narrator writing under the Antonines, such as Plutarch or Pausanias, with citations of the classical sources. The literary quality of these retellings is generally praised.

Each myth is followed by Graves's interpretation of its origin and significance, following his theories on a prehistoric Matriarchal religion as presented in his book White Goddess and elsewhere. These theories and his etymologies are generally rejected by classical scholars, but Graves dismissed such criticism, arguing that by definition classical scholars lack "the poetic capacity to forensically examine mythology".[1]

Each myth is presented in the voice of a narrator writing under the Antonines, such as Plutarch or Pausanias, with citations of the classical sources. The literary quality of these retellings is generally praised.

Each myth is followed by Graves's interpretation of its origin and significance, following his theories on a prehistoric Matriarchal religion as presented in his book White Goddess and elsewhere. These theories and his etymologies are generally rejected by classical scholars, but Graves dismissed such criticism, arguing that by definition classical scholars lack "the poetic capacity to forensically examine mythology".[1]

The myth

In the beginning, Eurynome, the Goddess of All Things, rose naked from Chaos, but found nothing substantial for her feet to rest upon, and therefore divided the sea from the sky, dancing lonely upon its waves. She danced towards the south, and the wind set in motion behind her seemed something new and apart with which to begin a work of creation. Wheeling about, she caught hold of this north wind, rubbed it between her hands, and behold! the great serpent Ophion. Eurynome danced to warm herself, wildly and more wildly, until Ophion, grown lustful, coiled about those divine limbs and was moved to couple with her. Now, the North Wind, who is also called Boreas, fertilizes; which is why mares often turn their hind-quarters to the wind and breed foals without aid of a stallion. So Eurynome was likewise got with child.

Next, she assumed the form of a dove, brooding on the waves and, in due process of time, laid the Universal Egg. At her bidding, Ophion coiled seven times about this egg, until it hatched and split in two. out tumbled all things that exist, her children: sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures.

Eurynome and Ophion made their home upon Mount Olympus, where he vexed her by claiming to be the author of the Universe. Forthwith she bruised his head with her heel, kicked out his teeth, and banished him to the dark caves below the earth.

Next, the goddess created the seven planetary powers, setting a Titaness and a Titan over each. Theia and Hyperion for the Sun; Phoebe and Atlas for the Moon; Dione and Crius for the planet Mars; Metis and Coeus for the planet Mercury; Themis and Eurynmedon for the planet Jupiter; Tethys and Oceanus for Venus; Rhea and Cronus for the planet Saturn. But the first man was Pelasgus, ancestor of the Pelasgians; he sprang from the soil of Arcadia, followed by certain others, whom he taught to make huts and feed upon acorns and sew pig-skin tunics such as poor folk still wear in Euboea and Phocis.

Next, she assumed the form of a dove, brooding on the waves and, in due process of time, laid the Universal Egg. At her bidding, Ophion coiled seven times about this egg, until it hatched and split in two. out tumbled all things that exist, her children: sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures.

Eurynome and Ophion made their home upon Mount Olympus, where he vexed her by claiming to be the author of the Universe. Forthwith she bruised his head with her heel, kicked out his teeth, and banished him to the dark caves below the earth.

Next, the goddess created the seven planetary powers, setting a Titaness and a Titan over each. Theia and Hyperion for the Sun; Phoebe and Atlas for the Moon; Dione and Crius for the planet Mars; Metis and Coeus for the planet Mercury; Themis and Eurynmedon for the planet Jupiter; Tethys and Oceanus for Venus; Rhea and Cronus for the planet Saturn. But the first man was Pelasgus, ancestor of the Pelasgians; he sprang from the soil of Arcadia, followed by certain others, whom he taught to make huts and feed upon acorns and sew pig-skin tunics such as poor folk still wear in Euboea and Phocis.

Graves's retellings have been widely praised as imaginative and poetic, but the scholarship behind his hypotheses and conclusions is sometimes criticised as idiosyncratic and untenable.[4] Ted Hughes and other poets have found the system of The White Goddess congenial; The Greek Myths contains about a quarter of that system, and does not include the method of composing poems.[5]

The Greek Myths has been heavily criticised both during and after the lifetime of the author. Critics have deprecated Graves's personal interpretations, which are, in the words of one of them, "either the greatest single contribution that has ever been made to the interpretation of Greek myth or else a farrago of cranky nonsense; I fear that it would be impossible to find any classical scholar who would agree with the former diagnosis". Graves's etymologies have been questioned, and his largely intuitive division between "true myth" and other sorts of story has been viewed as arbitrary, taking myths out of the context in which we now find them. The basic assumption that explaining mythology requires any "general hypothesis", whether Graves's or some other, has also been disputed.[6] The work was called a compendium of misinterpretations.[7] Robin Hard called it "comprehensive and attractively written," but added that "the interpretive notes are of value only as a guide to the author's personal mythology".[8] Michael W. Pharand, quoting some of the earlier criticisms, rebutted them: "Graves's theories and conclusions, outlandish as they seemed to his contemporaries (or may appear to us), were the result of careful observation."[9]

H. J. Rose, agreeing with several of the above critics, questions the scholarship of the retellings. Graves presents The Greek Myths as an updating of William Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (originally published 1844) and calls it still "the standard work in English", never brought up to date: Rose is dismayed to find no sign that Graves had heard of the Oxford Classical Dictionary or any of the "various compendia of mythology, written in, or translated into, our tongue since 1844". Rose finds many omissions and some clear errors, most seriously Graves's ascribing to Sophocles the argument of his Ajax (Graves §168.4); this evaluation has been repeated by other critics since.[10]

The Greek Myths has been heavily criticised both during and after the lifetime of the author. Critics have deprecated Graves's personal interpretations, which are, in the words of one of them, "either the greatest single contribution that has ever been made to the interpretation of Greek myth or else a farrago of cranky nonsense; I fear that it would be impossible to find any classical scholar who would agree with the former diagnosis". Graves's etymologies have been questioned, and his largely intuitive division between "true myth" and other sorts of story has been viewed as arbitrary, taking myths out of the context in which we now find them. The basic assumption that explaining mythology requires any "general hypothesis", whether Graves's or some other, has also been disputed.[6] The work was called a compendium of misinterpretations.[7] Robin Hard called it "comprehensive and attractively written," but added that "the interpretive notes are of value only as a guide to the author's personal mythology".[8] Michael W. Pharand, quoting some of the earlier criticisms, rebutted them: "Graves's theories and conclusions, outlandish as they seemed to his contemporaries (or may appear to us), were the result of careful observation."[9]

H. J. Rose, agreeing with several of the above critics, questions the scholarship of the retellings. Graves presents The Greek Myths as an updating of William Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (originally published 1844) and calls it still "the standard work in English", never brought up to date: Rose is dismayed to find no sign that Graves had heard of the Oxford Classical Dictionary or any of the "various compendia of mythology, written in, or translated into, our tongue since 1844". Rose finds many omissions and some clear errors, most seriously Graves's ascribing to Sophocles the argument of his Ajax (Graves §168.4); this evaluation has been repeated by other critics since.[10]

Phanes Protogonos, first born

Phanes Protogonos, first born

Graves interpreted Bronze Age Greece as changing from a matriarchal society under the Pelasgians to a patriarchal one under continual pressure from victorious Greek-speaking tribes. In the second stage local kings came to each settlement as foreign princes, reigned by marrying the hereditary queen, who represented the Triple Goddess, and were ritually slain by the next king after a limited period, originally six months. Kings managed to evade the sacrifice for longer and longer periods, often by sacrificing substitutes, and eventually converted the queen, priestess of the Goddess, into a subservient and chaste wife, and in the final stage had legitimate sons to reign after them.

The Greek Myths presents the myths as stories from the ritual of all three stages, and often as historical records of the otherwise unattested struggles between Greek kings and the Moon-priestesses. In some cases Graves conjectures a process of "iconotropy", or image-turning, by which a hypothetical cult image of the matriarchal or matrilineal period has been misread by later Greeks in their own terms. Thus, for example, he conjectures an image of divine twins struggling in the womb of the Horse-Goddess, which later gave rise to the myth of the Trojan Horse.

Pelasgian creation mythGraves's imaginatively reconstructed "Pelasgian creation myth" features a supreme creatrix, Eurynome, "The Goddess of All Things",[2] who rises naked from Chaos to part sea from sky so that she can dance upon the waves. Catching the north wind at her back and rubbing it between her hands, she warms the pneuma and spontaneously generates the serpent Ophion, who mates with her. In the form of a dove upon the waves she lays the Cosmic Egg and bids Ophion to incubate it by coiling seven times around until it splits in two and hatches "all things that exist ... sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures".[3]

In the soil of Arcadia the Pelasgians spring up from Ophion's teeth, scattered under the heel of Eurynome, who kicked the serpent from their home on Mount Olympus for his boast of having created all things. Eurynome, whose name means "wide wandering", sets male and female Titans for each wandering planet: Theia and Hyperion for the Sun; Phoebe and Atlas for the Moon; Metis and Coeus for Mercury; Tethys and Oceanus for Venus; Dione and Crius for Mars; Themis and Eurymedon for Jupiter; and Rhea and Cronus for Saturn.[2]

The Greek Myths presents the myths as stories from the ritual of all three stages, and often as historical records of the otherwise unattested struggles between Greek kings and the Moon-priestesses. In some cases Graves conjectures a process of "iconotropy", or image-turning, by which a hypothetical cult image of the matriarchal or matrilineal period has been misread by later Greeks in their own terms. Thus, for example, he conjectures an image of divine twins struggling in the womb of the Horse-Goddess, which later gave rise to the myth of the Trojan Horse.

Pelasgian creation mythGraves's imaginatively reconstructed "Pelasgian creation myth" features a supreme creatrix, Eurynome, "The Goddess of All Things",[2] who rises naked from Chaos to part sea from sky so that she can dance upon the waves. Catching the north wind at her back and rubbing it between her hands, she warms the pneuma and spontaneously generates the serpent Ophion, who mates with her. In the form of a dove upon the waves she lays the Cosmic Egg and bids Ophion to incubate it by coiling seven times around until it splits in two and hatches "all things that exist ... sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures".[3]

In the soil of Arcadia the Pelasgians spring up from Ophion's teeth, scattered under the heel of Eurynome, who kicked the serpent from their home on Mount Olympus for his boast of having created all things. Eurynome, whose name means "wide wandering", sets male and female Titans for each wandering planet: Theia and Hyperion for the Sun; Phoebe and Atlas for the Moon; Metis and Coeus for Mercury; Tethys and Oceanus for Venus; Dione and Crius for Mars; Themis and Eurymedon for Jupiter; and Rhea and Cronus for Saturn.[2]

Also see

- Pelasgians

- Illyrians

- Myth of Illyrious

References

- The White Goddess, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, p. 224. ISBN 0-374-50493-8

- ^ Jump up to:a b Graves, Robert (1990) [1955]. The Greek Myths 1. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-001026-8.

- "Books: The Goddess & the Poet". TIME. 18 July 1955. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- "The stories themselves have been presented in a lively and attractive manner, with an effect of candour and intimacy very like that of Samuel Butler's translations of Homer." Review by Jay Macpherson, Phoenix, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Spring, 1958), pp. 15–25. JSTOR link. "the paraphrases themselves are wittily written, and take a twinkly delight in promoting extra-canonical alternative versions of familiar stories." Nick Lowe, "Killing the Graves Myth", Times Online, 20 December 2005. Times Online

- Graves and the Goddess, ed. Firla and Lindop, Susquehanna Univ. Press, 2003.

- Robin Hard, bibliographical notes to his edition of H.J. Rose, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology, p. 690, ISBN 0-415-18636-6, quoted.G.S. Kirk, Myth: its meaning and functions in ancient and other cultures, Cambridge University Press, 1970, p. 5. ISBN 0-520-02389-7

Richard G. A. Buxton, Imaginary Greece: The Contexts of Mythology, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 5. ISBN 0-521-33865-4

Mary Lefkowitz, Greek Gods, Human Lives

Kevin Herbert: review of TGM; The Classical Journal, Vol. 51, No. 4. (Jan. 1956), pp. 191–192. JSTOR link. - As quoted in: Pharand, Michael W. "Greek Myths, White Goddess: Robert Graves Cleans up a 'Dreadful Mess'", in Ian Ferla and Grevel Lindop (ed.) (2003). Graves and the Goddess: Essays on Robert Graves's The White Goddess. Associated University Presses. p.183.

- Hard, Robin. The Library of Greek Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1997. p.xxxii.

- Pharand, Michael W. "Greek Myths, White Goddess: Robert Graves Cleans up a 'Dreadful Mess'", in Ian Ferla and Grevel Lindop (ed), Graves and the Goddess: Essays on Robert Graves's The White Goddess. Associated University Presses, 2003. p.188.

- H. J. Rose, Review of "'The Greek Myths"; The Classical Review, New Ser., Vol. 5, No. 2. (Jun. 1955), pp. 208–209. JSTOR link. For other criticisms of the accuracy of Graves' retellings, see for example, Nick Lowe, "Killing the Graves Myth", Times Online, 20 December 2005. Times Online Lowe called the work "pseudo-scholarly".