Brief history

Quick overview

The history of Albania emerges from the pre-history of the Balkan states more than 3000 BC, with early records of Illyria in Greco-Roman historiography. It's identity stretched widely over the Balkan peninsula and gradually got smaller in the present day western Balkans. The modern territory of Albania had no counterpart in the standard political divisions of classical antiquity. Rather, its modern boundaries correspond to parts of the ancient Roman provinces of Dalmatia (southern Illyricum), Macedonia (particularly Epirus Nova), and Moesia Superior. The territory remained under Roman and Byzantine control until the Slavic migrations of the 7th century. It was integrated into the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century.

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state was formed in the Middle Ages as the Principality of Arbër and a Sicilian dependency known as the medieval Kingdom of Albania. The area was part of the Serbian Empire, but passed to the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. It remained under Ottoman control as part of the province of Rumelia until 1912, when the first independent Albanian state was founded by an Albanian Declaration of Independence following a short occupation by the Kingdom of Serbia.[1] The formation of an Albanian national consciousness dates to the later 19th century and is part of the larger phenomenon of the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

A short-lived monarchical state known as the Principality of Albania (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). Another monarchy, the Kingdom of Albania (1928–39), replaced the republic. The country endured an occupation by Italy just prior to World War II. After the collapse of the Axis powers, Albania became a communist state, the Socialist People's Republic of Albania, which for most of its duration was dominated by Enver Hoxha (died 1985). Hoxha's political heir Ramiz Alia oversaw the disintegration of the "Hoxhaist" state during the wider collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

The communist regime collapsed in 1990, and the former communist Party of Labour of Albania was routed in elections in March 1992, amid economic collapse and social unrest. The unstable economic situation led to an Albanian diaspora, mostly to Italy,Greece, Switzerland, Germany and North America during the 1990s. The crisis peaked in the Albanian Turmoil of 1997. An amelioration of the economic and political conditions in the early years of the 21st century enabled Albania to become a full member of NATO in 2009. The country is applying to join the European Union.

The history of Albania emerges from the pre-history of the Balkan states more than 3000 BC, with early records of Illyria in Greco-Roman historiography. It's identity stretched widely over the Balkan peninsula and gradually got smaller in the present day western Balkans. The modern territory of Albania had no counterpart in the standard political divisions of classical antiquity. Rather, its modern boundaries correspond to parts of the ancient Roman provinces of Dalmatia (southern Illyricum), Macedonia (particularly Epirus Nova), and Moesia Superior. The territory remained under Roman and Byzantine control until the Slavic migrations of the 7th century. It was integrated into the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century.

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state was formed in the Middle Ages as the Principality of Arbër and a Sicilian dependency known as the medieval Kingdom of Albania. The area was part of the Serbian Empire, but passed to the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. It remained under Ottoman control as part of the province of Rumelia until 1912, when the first independent Albanian state was founded by an Albanian Declaration of Independence following a short occupation by the Kingdom of Serbia.[1] The formation of an Albanian national consciousness dates to the later 19th century and is part of the larger phenomenon of the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

A short-lived monarchical state known as the Principality of Albania (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). Another monarchy, the Kingdom of Albania (1928–39), replaced the republic. The country endured an occupation by Italy just prior to World War II. After the collapse of the Axis powers, Albania became a communist state, the Socialist People's Republic of Albania, which for most of its duration was dominated by Enver Hoxha (died 1985). Hoxha's political heir Ramiz Alia oversaw the disintegration of the "Hoxhaist" state during the wider collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

The communist regime collapsed in 1990, and the former communist Party of Labour of Albania was routed in elections in March 1992, amid economic collapse and social unrest. The unstable economic situation led to an Albanian diaspora, mostly to Italy,Greece, Switzerland, Germany and North America during the 1990s. The crisis peaked in the Albanian Turmoil of 1997. An amelioration of the economic and political conditions in the early years of the 21st century enabled Albania to become a full member of NATO in 2009. The country is applying to join the European Union.

Present day country

Albania ( al-bay-nee-ə,; Albanian: Shqipëri/Shqipëria; Gheg Albanian: Shqipni/Shqipnia), officially known as the Republic of Albania (Albanian: Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, Former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia to the east, and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea to the west and on the Ionian Sea to the southwest. It is less than 72 km (45 mi) from Italy, across the Strait of Otranto which links the Adriatic Sea to the Ionian Sea.

The Flag

This is the most recent version of the Albanian flag out of a long history of the similar Albanian flags used. The flag features a double-headed eagle in black, on a red background. This design is traced back to the royal seal of the noble house of George Castrioti Skanderbeg, an Albanian King, and a 15th century Turkish general. The symbol represented the supreme deity and has its roots deep into the Albanian culture and traces its origin from the Ilirio-Pelasgian antiquity and it is part of the Albanian cultural heritage, hence the Albanian flag. The symbol was also adopted by the Roman Emperor Constantine I (Saint Constantine The Great), being of Illyrian origin, this is said to be also the symbol of his family which he turn into into the symbol of the Byzantine Empire with the capital city named after him, Constantinople.

Note that Albanians call their country Shqipëria, meaning "Land of the Eagle."

Note that Albanians call their country Shqipëria, meaning "Land of the Eagle."

Etymology

Albania is the Medieval Latin name of the country, which is called Shqipëria by its people, from Medieval Greek Ἀλβανία Albania, besides variants Albanitia or Arbanitia.

The name may be derived from the Illyrian tribe of the Albani recorded by Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria who drafted a map in 150 AD[14] that shows the city of Albanopolis[15] (located northeast of Durrës).

The name may have a continuation in the name of a medieval settlement called Albanon and Arbanon, although it is not certain this was the same place.[16] In his History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates was the first to refer to Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium.[17] During the Middle Ages, the Albanians called their country Arbëri or Arbëni and referred to themselves as Arbëresh or Arbënesh.[18][19]

As early as the 17th century the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëresh. The two terms are popularly interpreted as "Land of the Eagles" and "Children of the Eagles".[20][21]

The name may be derived from the Illyrian tribe of the Albani recorded by Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria who drafted a map in 150 AD[14] that shows the city of Albanopolis[15] (located northeast of Durrës).

The name may have a continuation in the name of a medieval settlement called Albanon and Arbanon, although it is not certain this was the same place.[16] In his History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates was the first to refer to Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium.[17] During the Middle Ages, the Albanians called their country Arbëri or Arbëni and referred to themselves as Arbëresh or Arbënesh.[18][19]

As early as the 17th century the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëresh. The two terms are popularly interpreted as "Land of the Eagles" and "Children of the Eagles".[20][21]

Ethnicity

The origin of the Albanians has been for some time a matter of dispute among historians which is something that has to do more with politics rather than academia. However, due to linguisics and genetic studies on the origin of the Albanian people, historians conclude that the Albanians are descendants of populations of the prehistoric Balkans, such as the Pelasgian race, via the various Illyrian, Dacian and/or Thracian tribes.[1] Little is known about these people, and they blended into one another in Thraco-Illyrian and Daco-Thracian contact zones even in antiquity.

Pre-History

The Pelasgians

The Albanian people are widely accepted by many historian as the direct decedents of the Pelasgain people via the Illyrian tribe of the Albani. The name Pelasgians (/pəˈlæzdʒiənz, -dʒənz, -ɡiənz/; Greek: Πελασγοί, Pelasgoí; singular: Πελασγός, Pelasgós) were the indigenous people of the Balkan Peninsula. Fathers to many nations, it was the name used by some ancient Greek writers to refer to populations that either were the ancestors of the Greeks or preceded the Greeks in Greece, "a hold-all term for any ancient, primitive and presumably indigenous people in the Greek world".[11] In general, "Pelasgian" has come to mean more broadly all the indigenous inhabitants of the Aegean Sea region and their cultures before the advent of the Greek language.[12] This is not an exclusive meaning, but other senses require identification when meant. During the classical period, enclaves under that name survived in several locations of mainland Greece, Crete, and other regions of the Aegean. Populations identified as "Pelasgian" spoke a language or languages that at the time Greeks identified as "barbaric", even though some ancient writers described the Pelasgians as Greeks. A tradition also survived that large parts of Greece had once been Pelasgian before being Hellenized. These parts generally fell within the ethnic domain that by the 5th century BC was attributed to those speakers of ancient Greek who were identified as Ionians.

The Illyrians

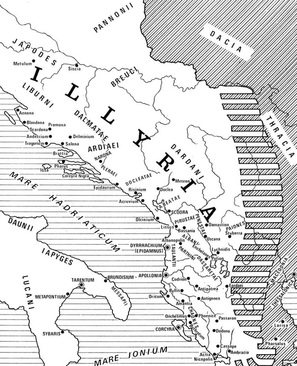

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of Indo-European tribes in antiquity of Pelasgian race, who inhabited part of the western Balkans and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula (Messapia). [1] The territory the Illyrians inhabited came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, who identified a territory that corresponds to the former Yugoslavia and Albania, between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of the Aoos (Vjosa) river in the south.[2] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC that describes coastal passages in the Mediterranean.[3]

These tribes, or at least a number of tribes considered "Illyrians proper" of which only small fragments are attested enough to classify it as a branch of Indo-European;[4] it was probably extinct by the 2nd century AD.[5]

The term "Illyrians" last appears in the historical record in the 7th century, referring to a Byzantine garrison operating within the former Roman province of Illyricum.[8] All the remaining tribes except perhaps the Romanized Vlachs[9] were Slavicised in the course of the early Middle Ages. The modern Albanian language is likely to have descended from a southern Illyrian dialect.[10][11]

The Albanian people are widely accepted by many historian as the direct decedents of the Pelasgain people via the Illyrian tribe of the Albani. The name Pelasgians (/pəˈlæzdʒiənz, -dʒənz, -ɡiənz/; Greek: Πελασγοί, Pelasgoí; singular: Πελασγός, Pelasgós) were the indigenous people of the Balkan Peninsula. Fathers to many nations, it was the name used by some ancient Greek writers to refer to populations that either were the ancestors of the Greeks or preceded the Greeks in Greece, "a hold-all term for any ancient, primitive and presumably indigenous people in the Greek world".[11] In general, "Pelasgian" has come to mean more broadly all the indigenous inhabitants of the Aegean Sea region and their cultures before the advent of the Greek language.[12] This is not an exclusive meaning, but other senses require identification when meant. During the classical period, enclaves under that name survived in several locations of mainland Greece, Crete, and other regions of the Aegean. Populations identified as "Pelasgian" spoke a language or languages that at the time Greeks identified as "barbaric", even though some ancient writers described the Pelasgians as Greeks. A tradition also survived that large parts of Greece had once been Pelasgian before being Hellenized. These parts generally fell within the ethnic domain that by the 5th century BC was attributed to those speakers of ancient Greek who were identified as Ionians.

The Illyrians

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of Indo-European tribes in antiquity of Pelasgian race, who inhabited part of the western Balkans and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula (Messapia). [1] The territory the Illyrians inhabited came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, who identified a territory that corresponds to the former Yugoslavia and Albania, between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of the Aoos (Vjosa) river in the south.[2] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC that describes coastal passages in the Mediterranean.[3]

These tribes, or at least a number of tribes considered "Illyrians proper" of which only small fragments are attested enough to classify it as a branch of Indo-European;[4] it was probably extinct by the 2nd century AD.[5]

The term "Illyrians" last appears in the historical record in the 7th century, referring to a Byzantine garrison operating within the former Roman province of Illyricum.[8] All the remaining tribes except perhaps the Romanized Vlachs[9] were Slavicised in the course of the early Middle Ages. The modern Albanian language is likely to have descended from a southern Illyrian dialect.[10][11]

The Trojan War

During the time of the Trojan War, the Pelasgians were known as the allies of the Trojans.

Rise of Alexander the Great

Born in Emathia of an Epiriote Princess, Alexander the son of Philip II of Macedon, was not a true heir of the throne of the Kingdom of Macedonia but rather was risen to power by his “arrogant, headstrong and meddlesome…” mother, Olympia, who was the driving force behind his success. Olympia, a wildly beautiful woman, was from the noble house the Molossians, direct decedents of Achilles, which explained Alexander’s obsession with the Trojan War and concurring of the East.

Phillip II, was a polygamist and his marriage to Olympia was a diplomatic move to establish peace and to settle the conflict among the Pelasgian tribes while also a strategic move to create an alliance with her uncle, the King of Epirus (Present day Albania). Even though Phillip fell in love with Olympia while being intimate with her during a religious ritual Snake Cult, likely mimicking the Pelasgian Myth of Creation, his relationship with Olympia was not a good one. Phillip regarded her as a “barbarian” and a sorceress and often would find her in bed with snakes. According to the writings of ancient writer Plutarch, this was how Alexander was conceived. He claims that Olympias was impregnated not by Philip, who was afraid of her and her affinity for sleeping in the company of snakes, but by Zeus. Plutarch (Alexander 2.2-3) relates that both Philip and Olympias dreamt of their son's future birth. Olympias dreamed of a loud burst of thunder and of lightning striking her womb. In Philip's dream, he sealed her womb with the seal of the lion. Hence the prophesied birth of Alexander is what gave him his name, “A le, si Ander” which in Pelasgian (Albanian) can be translated as “born like the dream”. The importance of his birth is also affirmed by Italian historian, Valerio Massimo Manfredi, in his bestseller book called “Alexander; Child of a Dream”.

Due to Phillip’s rough nature, aggression toward's Olympia and taunting of him, young Alexander found affinity on his mother's side and looked up to a father figure in Olympia's kin, his first mentor, Leonidas of Epirus. It wasn't until he rode the horse that no man could, when Olympia finally convinced Phillip that their son needed more than just military training. It was then when Phillip sough out the best tutor for him; the one who spoke the mother tongue and who studied under Plato, the Thracian Aristotle. It was through Aristotle that Alexander learned how to "speak Greek" and about the Hellenic culture. After the death of Phillip, the proclaimed son of Zeus and that of the princess of Epirus, claimed the throne of Macedon and went to conquer the known world. He was known as Alexander of Emathia (of the Great one) or simply, Alexander the Great.

Phillip II, was a polygamist and his marriage to Olympia was a diplomatic move to establish peace and to settle the conflict among the Pelasgian tribes while also a strategic move to create an alliance with her uncle, the King of Epirus (Present day Albania). Even though Phillip fell in love with Olympia while being intimate with her during a religious ritual Snake Cult, likely mimicking the Pelasgian Myth of Creation, his relationship with Olympia was not a good one. Phillip regarded her as a “barbarian” and a sorceress and often would find her in bed with snakes. According to the writings of ancient writer Plutarch, this was how Alexander was conceived. He claims that Olympias was impregnated not by Philip, who was afraid of her and her affinity for sleeping in the company of snakes, but by Zeus. Plutarch (Alexander 2.2-3) relates that both Philip and Olympias dreamt of their son's future birth. Olympias dreamed of a loud burst of thunder and of lightning striking her womb. In Philip's dream, he sealed her womb with the seal of the lion. Hence the prophesied birth of Alexander is what gave him his name, “A le, si Ander” which in Pelasgian (Albanian) can be translated as “born like the dream”. The importance of his birth is also affirmed by Italian historian, Valerio Massimo Manfredi, in his bestseller book called “Alexander; Child of a Dream”.

Due to Phillip’s rough nature, aggression toward's Olympia and taunting of him, young Alexander found affinity on his mother's side and looked up to a father figure in Olympia's kin, his first mentor, Leonidas of Epirus. It wasn't until he rode the horse that no man could, when Olympia finally convinced Phillip that their son needed more than just military training. It was then when Phillip sough out the best tutor for him; the one who spoke the mother tongue and who studied under Plato, the Thracian Aristotle. It was through Aristotle that Alexander learned how to "speak Greek" and about the Hellenic culture. After the death of Phillip, the proclaimed son of Zeus and that of the princess of Epirus, claimed the throne of Macedon and went to conquer the known world. He was known as Alexander of Emathia (of the Great one) or simply, Alexander the Great.

Pyrrhus the Eagle

He was from the tribe of the Molossians and related to Alexander the Great from his mother’s side. Was almost also named Alexander, he was an exceptional general and the only one who defeated the Romans in their own soil. His victory came at a devastating loss of his army. From this, we get the modern term “Pyrrhic Victory”, a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. He was the prince of Epirus and only 3 years old when his family was killed in an uprising. His was saved by the Illyrian King Glaucus, of the Taulanti, who adopted the boy and raised among his sons. Testimony of the kinship along the Illyrians and Epiriotes, is showed when King Glaucus places him at the throne of Epirus at the age of 17.

He inherited the name which we know him to today, Pyrrhus. It is likely that the name was a Roman pronunciation as in the language of his people, he was called “Pirro”. Historian ****** suggests that this name is a modern corruption of the word “burro” which in Albanian means “man”. Because Pyrrhus was so young and the only surviving heir of the monarchy of Epirus, being that he was adopted by the Illyrian King, Glaucia. While in the court of the Illyrian palace, he learned the art of warfare and launched his military complains which skills matched only to his cousin, Alexander the Great.

After returning home gloriously from one of his battles, Pyrrhus enjoyed his fame and reputation, and being called "Eagle" by the Epirots, "By you," said he, "I am an eagle; for how should I not be such, while I have your arms as wings to sustain me?" [92] Essentially implying that his people were all "Eagles", the nickname "Shqipe" (Eagle) which is still used among Albanians to show respect towards one another.

After returning home gloriously from one of his battles, Pyrrhus enjoyed his fame and reputation, and being called "Eagle" by the Epirots, "By you," said he, "I am an eagle; for how should I not be such, while I have your arms as wings to sustain me?" [92] Essentially implying that his people were all "Eagles", the nickname "Shqipe" (Eagle) which is still used among Albanians to show respect towards one another.

The Illyrian Wars

In the First Illyrian War, which lasted from 229[45] BC to 228 BC, Rome's concern with the trade routes running across the Adriatic Sea increased after the First Punic War, when many tribes of Illyria became united under one queen,[46] Teuta. The death of a Roman envoy named Coruncanius[47] on the orders of Teuta [48] and the attack on trading vessels owned by Italian merchants under Rome's protection, prompted the Roman senate to dispatch a Roman army under the command of the consuls Lucius Postumius Albinus (consul 234 and 229 BC) and Gnaeus Fulvius Centumalus. Rome expelled Illyrian garrisons at the cities of Epidamnus, Apollonia, Korkyra, Pharos and others and established a protectorate over these Greek towns.

The Romans also set up[49] Demetrius of Pharos as a power in Illyria to counterbalance the power of Teuta.[50]

The Second Illyrian War lasted from 220 BC to 219 BC. In 219 BC the Roman Republic was at war with the Celts of Cisalpine Gaul, and the Second Punic War with Carthage[51] was beginning. These distractions gave Demetrius the time he needed to build a new Illyrian war fleet. Leading this fleet of 90 ships, Demetrius sailed south of Lissus, violating his earlier treaty and starting the war.[52]

During the Third Illyrian War in 168 BC the Illyrian king Gentius allied himself with the Macedonians. First in 171 BC, he was allied with the Romans against the Macedonians, but in 169 he changed sides and allied himself with Perseus of Macedon. He arrested two Roman legati and destroyed the cities of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium, which were allied with Rome. In 168 he was defeated at Scodra by a Roman force under L. Anicius Gallus,[58] and in 167 brought to Rome as a captive to participate in Gallus' triumph, after which he was interned in Iguvium. In the Illyrian War of 229 BC, 219 BC and 168 BC, Rome overran the Illyrian settlements and suppressed piracy,[59] which had made Adriatic Sea an unsafe region for Roman commerce. There were three Roman campaigns: the first against Teuta the second against Demetrius of Pharos[60] and the third against Gentius. The first Roman campaign of 229 BC marked the first time that the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic in order to launch the invasion.[61]

The Romans also set up[49] Demetrius of Pharos as a power in Illyria to counterbalance the power of Teuta.[50]

The Second Illyrian War lasted from 220 BC to 219 BC. In 219 BC the Roman Republic was at war with the Celts of Cisalpine Gaul, and the Second Punic War with Carthage[51] was beginning. These distractions gave Demetrius the time he needed to build a new Illyrian war fleet. Leading this fleet of 90 ships, Demetrius sailed south of Lissus, violating his earlier treaty and starting the war.[52]

During the Third Illyrian War in 168 BC the Illyrian king Gentius allied himself with the Macedonians. First in 171 BC, he was allied with the Romans against the Macedonians, but in 169 he changed sides and allied himself with Perseus of Macedon. He arrested two Roman legati and destroyed the cities of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium, which were allied with Rome. In 168 he was defeated at Scodra by a Roman force under L. Anicius Gallus,[58] and in 167 brought to Rome as a captive to participate in Gallus' triumph, after which he was interned in Iguvium. In the Illyrian War of 229 BC, 219 BC and 168 BC, Rome overran the Illyrian settlements and suppressed piracy,[59] which had made Adriatic Sea an unsafe region for Roman commerce. There were three Roman campaigns: the first against Teuta the second against Demetrius of Pharos[60] and the third against Gentius. The first Roman campaign of 229 BC marked the first time that the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic in order to launch the invasion.[61]

Roman Conquest and Administration

The Roman Navy's first crossing of the Adriatic Sea in 229 BC[6] involved Rome's first invasion of Illyria, the First Illyrian War. The Roman Republic finally completed the conquest of Illyria in 168 BC by defeating the army of the Illyrian king Gentius. Shortly after the whole Illyrian (Balkan) peninsula was incorporated into the Roman Prefecture of Illyricum where the present day ethnic Albanian region was divided into the administrative provinces of Illyria, Macedonia, Dardania and Epirus.

Roman Emperors with Illyrian Origin

Distinguishing themselves as prominent warriors, the Illyrian soldiers moved up the ranks as became generals and then emperors of the Roman Empire. The Illyriciani or Illyrian Emperors, as they were otherwise know as, were a group of Roman emperors during the Crisis of the Third Century who hailed from the region of Illyricum (the modern western Balkans), and were raised chiefly from the ranks of the Roman army (whence they are ranked among the so-called "barracks emperors").[1] In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the Illyricum and the other Danubian provinces (Raetia, Pannonia, Moesia) held the largest concentration of Roman forces (12 legions, up to a third of the total army), and were a major recruiting ground. .

The historical period of the Illyrian emperors proper begins with Claudius Gothicus in 268 and ends in 284 with the rise of Diocletian and the institution of the Tetrarchy.[2] This rather short period was very important in the history of the Empire, since it represents the recovery from the Crisis of the Third Century, a long period of usurpations and military difficulties. All of the Illyrian emperors were trained and able soldiers, and they recovered some of the provinces and positions lost by their predecessors, including Gaul and the eastern provinces. Men of Illyrian or Thraco-Dacian origin however continued to be prominent in the Empire throughout the 4th century and beyond.

The historical period of the Illyrian emperors proper begins with Claudius Gothicus in 268 and ends in 284 with the rise of Diocletian and the institution of the Tetrarchy.[2] This rather short period was very important in the history of the Empire, since it represents the recovery from the Crisis of the Third Century, a long period of usurpations and military difficulties. All of the Illyrian emperors were trained and able soldiers, and they recovered some of the provinces and positions lost by their predecessors, including Gaul and the eastern provinces. Men of Illyrian or Thraco-Dacian origin however continued to be prominent in the Empire throughout the 4th century and beyond.

Arrival of Christianity

Christianity first came to the area when Saint Paul and some of his followers traveled in the Balkans passing through Thracian and Greek and Albanian populated areas. He spread Christianity to the people of Beroia, Epirus, Thessaloniki, Athens, Corinth and Durrës (Dyrrachium).

Paul went through the Roman Province of Macedonia (Present day Albania) into Achaea and made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of Jews who had made a plot against him. At this time (56–57), it is likely that Paul visited Corinth for three months.[18] In Romans 15:19 Paul wrote that he visited Illyricum, but he may have meant what would now be called Illyria Graeca,[71] which lay in the northern part of modern Albania, but was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.[72]

The Christian gospel may have also reached Albania through the Illyrian soldiers who predominated in the famous Praetorian Guard. These men were housed in their barracks called the "Praetorium", and were responsible for guarding the palaces of the Roman emperors and governors.

These imperial guards had two excellent opportunities to become acquainted with the new Christian religion.

First, when the Roman provincial governor Pilate turned Jesus Christ over to the soldiers for crucifixion, they "led him away into the hall called Praetorium, and called together the whole band" (Mark 15:16). The brutal soldiery mocked, abused and finally crucified their captive. And it was one of them who at Christ's death finally expressed what others of their number must have concluded by then: "Truly this man was the Son of God!" (Mark 15:39)

Paul went through the Roman Province of Macedonia (Present day Albania) into Achaea and made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of Jews who had made a plot against him. At this time (56–57), it is likely that Paul visited Corinth for three months.[18] In Romans 15:19 Paul wrote that he visited Illyricum, but he may have meant what would now be called Illyria Graeca,[71] which lay in the northern part of modern Albania, but was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.[72]

The Christian gospel may have also reached Albania through the Illyrian soldiers who predominated in the famous Praetorian Guard. These men were housed in their barracks called the "Praetorium", and were responsible for guarding the palaces of the Roman emperors and governors.

These imperial guards had two excellent opportunities to become acquainted with the new Christian religion.

First, when the Roman provincial governor Pilate turned Jesus Christ over to the soldiers for crucifixion, they "led him away into the hall called Praetorium, and called together the whole band" (Mark 15:16). The brutal soldiery mocked, abused and finally crucified their captive. And it was one of them who at Christ's death finally expressed what others of their number must have concluded by then: "Truly this man was the Son of God!" (Mark 15:39)

The Arrival of Slavs

The Slavs migrated in successive waves. Small numbers might have moved down as early as the 3rd century however the bulk of migration did not occur until the late 6th century AD. Very little is know of their origin, but they occupied most of the Eastern Roman Empire, pushing downwards the Roman Province of Illyricum towards present day Greece. Most still remained subjects of the Roman Empire, but those that settled in the Pannonian plain were tributary to the Avars.

By the 6th Century, the numbers of Illyrian people were greatly decreased by the previous barbarian incursions which left a vacuum later to be filled by southern slavs. This caused the remaining Illyrian tribes to either assimilate or push southward to present day Albania. Many fled to mountainous areas or to the refuges of the cities on the Adriatic coast. When the Slavs arrived, they were the first barbarian tribes to actually settle in the area permanently. They assimilated many of the native Balkan people.[25][26] However those who ventured downward and took to the mountains of southern Illyria, found refuge among their kin and retained their own cultures and language: scholars believe that these tribes are the ancestors of the Albanian people.

By the 6th Century, the numbers of Illyrian people were greatly decreased by the previous barbarian incursions which left a vacuum later to be filled by southern slavs. This caused the remaining Illyrian tribes to either assimilate or push southward to present day Albania. Many fled to mountainous areas or to the refuges of the cities on the Adriatic coast. When the Slavs arrived, they were the first barbarian tribes to actually settle in the area permanently. They assimilated many of the native Balkan people.[25][26] However those who ventured downward and took to the mountains of southern Illyria, found refuge among their kin and retained their own cultures and language: scholars believe that these tribes are the ancestors of the Albanian people.

The Byzantine Period

In 395, the Roman Empire was permanently divided and the area that now constitutes modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire.

Since the 1st and 2nd century, Christianity had become the established religion in most of the eastern Roman Empire, supplanting pagan polytheism. But, though the country was in the fold of Byzantium, Christians in the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Pope of Rome until 732. In that year the iconoclast Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isaurian, angered by archbishops of the region because they had supported Rome in the Iconoclastic Controversy, detached the church of the province from the Roman pope and placed it under the patriarch of Constantinople. When the Christian church split in 1054 between the East and Rome,the region of southern Albania retained its ties to Constantinople while the north reverted to the jurisdiction of Rome. This split marked the first significant religious fragmentation of the country.

Later, in the early 9th century, the Byzantine government established the theme of Dyrrhachium, based in the city of the same name and covering most of the coast, while the interior was left under Slavic and later Bulgarian control. Full Byzantine control over modern Albania was established only after the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria in the early 11th century.

In his History written in 1079-1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[2] However a later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion in 1078, is undisputed.[3] At this point, they are already fully Christianized. In the late 11th and 12th centuries, the region played a crucial part in the Byzantine–Norman Wars; Dyrrhachium was the westernmost terminus of the Via Egnatia, the main overland route to Constantinople, and was one of the main targets of the Normans (cf. Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081)). Towards the end of the 12th century, as Byzantine central authority weakened and rebellions and regionalist secessionism became more common, the region of Arbanon became an autonomous principality ruled by its own hereditary princes.

After the Fourth Crusade, the region came under the control of the Despotate of Epirus, but its control was never firm. Serbian influence began to be strongly felt at this time, as well as those of Venice and later of the Kingdom of Sicily, as both powers tried to gain control of coastal Albania for their purposes.

The new administrative system of the themes, or military provinces created by the Byzantine Empire, contributed to the eventual rise of feudalism in Albania, as peasant soldiers who served military lords became serfs on their landed estates. Among the leading families of the Albanian feudal nobility were the Thopias, Balshas, Shpatas, Muzakas, Aranitis, Dukagjins, and Kastriotis. The first three of these rose to become rulers of principalities that were practically independent of Byzantium.[4]

In 1258, the Sicilians took possession of the island of Corfu and the Albanian coast, from Dyrrhachium to Valona and Buthrotum and as far inland as Berat. This foothold, reformed in 1272 as the "Kingdom of Albania", was intended by the dynamic Sicilian ruler,Charles of Anjou, to become the launchpad for an overland invasion of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines however managed to recover most of Albania by 1274, leaving only Valona and Dyrrhachium in Charles' hands. Finally, when Charles launched his much-delayed advance, it was stopped at the Siege of Berat in 1280–1281. Albania would remain largely under Byzantine control until the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347, when it fell to the hands of the Serbian ruler Stephen Dushan and became part of the Serbian Empire.

Since the 1st and 2nd century, Christianity had become the established religion in most of the eastern Roman Empire, supplanting pagan polytheism. But, though the country was in the fold of Byzantium, Christians in the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Pope of Rome until 732. In that year the iconoclast Byzantine emperor Leo III the Isaurian, angered by archbishops of the region because they had supported Rome in the Iconoclastic Controversy, detached the church of the province from the Roman pope and placed it under the patriarch of Constantinople. When the Christian church split in 1054 between the East and Rome,the region of southern Albania retained its ties to Constantinople while the north reverted to the jurisdiction of Rome. This split marked the first significant religious fragmentation of the country.

Later, in the early 9th century, the Byzantine government established the theme of Dyrrhachium, based in the city of the same name and covering most of the coast, while the interior was left under Slavic and later Bulgarian control. Full Byzantine control over modern Albania was established only after the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria in the early 11th century.

In his History written in 1079-1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[2] However a later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion in 1078, is undisputed.[3] At this point, they are already fully Christianized. In the late 11th and 12th centuries, the region played a crucial part in the Byzantine–Norman Wars; Dyrrhachium was the westernmost terminus of the Via Egnatia, the main overland route to Constantinople, and was one of the main targets of the Normans (cf. Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081)). Towards the end of the 12th century, as Byzantine central authority weakened and rebellions and regionalist secessionism became more common, the region of Arbanon became an autonomous principality ruled by its own hereditary princes.

After the Fourth Crusade, the region came under the control of the Despotate of Epirus, but its control was never firm. Serbian influence began to be strongly felt at this time, as well as those of Venice and later of the Kingdom of Sicily, as both powers tried to gain control of coastal Albania for their purposes.

The new administrative system of the themes, or military provinces created by the Byzantine Empire, contributed to the eventual rise of feudalism in Albania, as peasant soldiers who served military lords became serfs on their landed estates. Among the leading families of the Albanian feudal nobility were the Thopias, Balshas, Shpatas, Muzakas, Aranitis, Dukagjins, and Kastriotis. The first three of these rose to become rulers of principalities that were practically independent of Byzantium.[4]

In 1258, the Sicilians took possession of the island of Corfu and the Albanian coast, from Dyrrhachium to Valona and Buthrotum and as far inland as Berat. This foothold, reformed in 1272 as the "Kingdom of Albania", was intended by the dynamic Sicilian ruler,Charles of Anjou, to become the launchpad for an overland invasion of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines however managed to recover most of Albania by 1274, leaving only Valona and Dyrrhachium in Charles' hands. Finally, when Charles launched his much-delayed advance, it was stopped at the Siege of Berat in 1280–1281. Albania would remain largely under Byzantine control until the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347, when it fell to the hands of the Serbian ruler Stephen Dushan and became part of the Serbian Empire.

Medieval Period

The territory now known as Albania remained under Roman (Byzantine) control until the Slavs began to overrun it from 548 and onward,[22] and was captured by Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century. After the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the Bulgarian Empire in the middle and late 13th century, some of the territory of modern-day Albania was captured by the Serbian Principality. In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in the lands that would become Albania.[23]

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state formed in the Middle Ages, as the Principality of Arbër and the Kingdom of Albania. The Principality of Arbër or Albanon (Albanian): Arbër or Arbëria, was the first Albanian state during the Middle Ages , it was established by archon Progon in the region of Kruja, in ca 1190. Progon, the founder, was succeeded by his sons Gjin and Demetrius, the latter which attained the height of the realm. After the death of Dhimiter, the last of the Progon family, the principality came under Gregory Kamonas, and later Golem. The Principality was dissolved in 1255.[24][25][26] Pipa and Repishti conclude that Arbanon was the first sketch of an "Albanian state", and that it retained semi-autonomous status as the western extremity of an empire (under the Doukai of Epirus or the Laskarids of Nicaea).[27]

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state formed in the Middle Ages, as the Principality of Arbër and the Kingdom of Albania. The Principality of Arbër or Albanon (Albanian): Arbër or Arbëria, was the first Albanian state during the Middle Ages , it was established by archon Progon in the region of Kruja, in ca 1190. Progon, the founder, was succeeded by his sons Gjin and Demetrius, the latter which attained the height of the realm. After the death of Dhimiter, the last of the Progon family, the principality came under Gregory Kamonas, and later Golem. The Principality was dissolved in 1255.[24][25][26] Pipa and Repishti conclude that Arbanon was the first sketch of an "Albanian state", and that it retained semi-autonomous status as the western extremity of an empire (under the Doukai of Epirus or the Laskarids of Nicaea).[27]

The Ottoman Invasion

Ottoman supremacy in the west Balkan region began in 1385 with the Battle of Savra. On the conquered part of Albania, which territory stretched between Mat River on the north and Çameria to the south, Ottoman Empire established the Sanjak of Albania[34] (also known as Arvanid Sancak) and in 1419 Gjirokastra became the county town of the Sanjak of Albania.[35] Beginning in the late-14th century, the Ottomans expanded their empire from Anatolia to the Balkans (Rumelia).

By the 15th century, the Ottomans ruled most of the Balkan Peninsula. Their advance in Albania was interrupted in the 15th century, when George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero who had served as an Ottoman military officer, renounced Ottoman service, allied with some Albanian chiefs forming the League of Lezhë and fought off successfully Turkish rule from 1443–1468 upon his death. Skanderbeg frustrated every attempt by the Turks to regain Albania, which they envisioned as a springboard for the invasion of Italy and western Europe. His unequal fight against the mightiest power of the time won the esteem of Europe as well as some support in the form of money and military aid from Naples, the papacy, Venice, and Ragusa.[36] Three major attacks (Siege of Krujë (1450), Second Siege of Krujë (1466–67), Third Siege of Krujë (1467)) suffered Albania during this period from major armies led by the great Ottoman sultans themselves, Murad II and Mehmed II The Conqueror. Albania was almost fully re-occupied by the Ottomans in 1479 after capturing Shkodër from Venice. Albania's conquest by Ottomans was completed after Durrës's capture from Venice in 1501.

By the 15th century, the Ottomans ruled most of the Balkan Peninsula. Their advance in Albania was interrupted in the 15th century, when George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero who had served as an Ottoman military officer, renounced Ottoman service, allied with some Albanian chiefs forming the League of Lezhë and fought off successfully Turkish rule from 1443–1468 upon his death. Skanderbeg frustrated every attempt by the Turks to regain Albania, which they envisioned as a springboard for the invasion of Italy and western Europe. His unequal fight against the mightiest power of the time won the esteem of Europe as well as some support in the form of money and military aid from Naples, the papacy, Venice, and Ragusa.[36] Three major attacks (Siege of Krujë (1450), Second Siege of Krujë (1466–67), Third Siege of Krujë (1467)) suffered Albania during this period from major armies led by the great Ottoman sultans themselves, Murad II and Mehmed II The Conqueror. Albania was almost fully re-occupied by the Ottomans in 1479 after capturing Shkodër from Venice. Albania's conquest by Ottomans was completed after Durrës's capture from Venice in 1501.

Albanian Resistance to the Ottoman Invasion

Given their skills as warriors, many Albanians had been recruited into the Janissary corps, including the feudal heir George Kastrioti who was renamed Skanderbeg (Iskandar Bey) by his Turkish trainers at Edirne. After some Ottoman defeats at the hands of the Hungarians, Skanderbeg deserted on November 1443 and began a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire.[37]

Battle of Albulena 1457

After deserting, Skanderbeg re-converted to Roman Catholicism and declared war against the Ottoman Empire,[37] which he led from 1443 to 1468. Under a red flag bearing Skanderbeg's heraldic emblem, an Albanian force held off Ottoman campaigns for twenty-five years and overcame sieges of Krujë led by major forces of the Ottoman sultans Murad II and Mehmed II.For 25 years Skanderbeg's 10,000 man army marched through Ottoman territory winning against consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces.[38] Throughout his rebellion,Skanderbeg defeated the ottomans in numerous battles such as in Torvioll, Oranik, Otonetë and Mokra.Hist most brilliant being in Albulena.

However, Skanderbeg was unable to receive any of the help which had been promised him by the popes or the Italian states, Venice, Naples and Milan. He died in 1468, leaving no worthy successor. After his death the rebellion continued, but without its former success. The loyalties and alliances created and nurtured by Skanderbeg faltered and fell apart and the Ottomans reconquered the territory of Albania, culminating with the siege of Shkodra in 1479. Shortly after the fall of the castles of northern Albania, many Albanians fled to neighboring Italy, giving rise to the modern Arbëreshë communities.

Skanderbeg’s long struggle to keep Albania free became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.[36]

Upon the Ottomans' return in 1479, a large number of Albanians fled to Italy, Egypt and other parts of the Ottoman Empire and Europe and maintained their Arbëresh identity. Many Albanians won fame and fortune as soldiers, administrators, and merchants in far-flung parts of the Empire. As the centuries passed, however, Ottoman rulers lost the capacity to command the loyalty of local pashas, which threatened stability in the region. The Ottoman rulers of the 19th century struggled to shore up central authority, introducing reforms aimed at harnessing unruly pashas and checking the spread of nationalist ideas. Albania would be a part of the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century.

The Ottoman Administration

After the death of Skanderbeg and more than a decade of fighting, Albania would eventually succumb to Ottoman rule. The Ottoman period that followed was characterized by harsh economic times, a change in the landscape through a gradual eastern modification of the culture with the introduction of bazaars, military garrisons and mosques in many Albanian regions. Both forced conversion and poor economic conditions, led parts of the Albanian population gradually converting to Islam, with many joining the sect of the military order of Islam called the Sufi Order of the Bektashi . Converting from Christianity to Islam brought considerable advantages, including access to Ottoman trade networks, bureaucratic positions and the army.

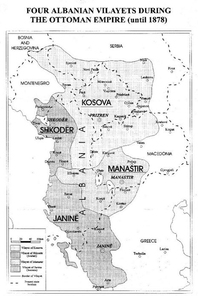

Because of their military talents, many Albanians where recruited to serve in the elite order of the Ottoman army called the Janissary unit and others in the administrative Devşirme system. Many Albanians moved up the military ranks and gained prominent positions in the Ottoman government, with no fewer than 42 Grand Viziers of the Empire were of Albanian descent. The Ottoman period also saw the rising of semi-autonomous Albanian ruled Pashaliks and Albanians were also an important part of the Ottoman army and Ottoman administration like the case of Köprülü family. Albania would remain a part of the Ottoman Empire as the provinces of Scutari, Monastir and Janina until 1912.

Rise of Nations

By the 1870s, the Sublime Porte's reforms aimed at checking the Ottoman Empire's disintegration had clearly failed. The image of the "Turkish yoke" had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the empire's Balkan peoples, and their march toward independence quickened. The Albanians, because of the higher degree of Islamic influence, their internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian-populated lands to the emerging Balkan states--Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece—were the last of the Balkan peoples to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[41]

However, in the 19th century after the fall of the Albanian pashaliks and the Massacre of the Albanian Beys an Albanian National Awakening took place and many revolts against the Ottoman Empire were organized. Such revolts included the Albanian Revolts of 1833-1839, the Revolt of 1843–44, and the Revolt of 1847. A culmination of the Albanian National Awakening were the League of Prizren and the League of Peja, but they were unsuccessful to an Albanian independence, which occurred only in 1912, through the Albanian Declaration of Independence.

Battle of Albulena 1457

After deserting, Skanderbeg re-converted to Roman Catholicism and declared war against the Ottoman Empire,[37] which he led from 1443 to 1468. Under a red flag bearing Skanderbeg's heraldic emblem, an Albanian force held off Ottoman campaigns for twenty-five years and overcame sieges of Krujë led by major forces of the Ottoman sultans Murad II and Mehmed II.For 25 years Skanderbeg's 10,000 man army marched through Ottoman territory winning against consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces.[38] Throughout his rebellion,Skanderbeg defeated the ottomans in numerous battles such as in Torvioll, Oranik, Otonetë and Mokra.Hist most brilliant being in Albulena.

However, Skanderbeg was unable to receive any of the help which had been promised him by the popes or the Italian states, Venice, Naples and Milan. He died in 1468, leaving no worthy successor. After his death the rebellion continued, but without its former success. The loyalties and alliances created and nurtured by Skanderbeg faltered and fell apart and the Ottomans reconquered the territory of Albania, culminating with the siege of Shkodra in 1479. Shortly after the fall of the castles of northern Albania, many Albanians fled to neighboring Italy, giving rise to the modern Arbëreshë communities.

Skanderbeg’s long struggle to keep Albania free became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom, and independence.[36]

Upon the Ottomans' return in 1479, a large number of Albanians fled to Italy, Egypt and other parts of the Ottoman Empire and Europe and maintained their Arbëresh identity. Many Albanians won fame and fortune as soldiers, administrators, and merchants in far-flung parts of the Empire. As the centuries passed, however, Ottoman rulers lost the capacity to command the loyalty of local pashas, which threatened stability in the region. The Ottoman rulers of the 19th century struggled to shore up central authority, introducing reforms aimed at harnessing unruly pashas and checking the spread of nationalist ideas. Albania would be a part of the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century.

The Ottoman Administration

After the death of Skanderbeg and more than a decade of fighting, Albania would eventually succumb to Ottoman rule. The Ottoman period that followed was characterized by harsh economic times, a change in the landscape through a gradual eastern modification of the culture with the introduction of bazaars, military garrisons and mosques in many Albanian regions. Both forced conversion and poor economic conditions, led parts of the Albanian population gradually converting to Islam, with many joining the sect of the military order of Islam called the Sufi Order of the Bektashi . Converting from Christianity to Islam brought considerable advantages, including access to Ottoman trade networks, bureaucratic positions and the army.

Because of their military talents, many Albanians where recruited to serve in the elite order of the Ottoman army called the Janissary unit and others in the administrative Devşirme system. Many Albanians moved up the military ranks and gained prominent positions in the Ottoman government, with no fewer than 42 Grand Viziers of the Empire were of Albanian descent. The Ottoman period also saw the rising of semi-autonomous Albanian ruled Pashaliks and Albanians were also an important part of the Ottoman army and Ottoman administration like the case of Köprülü family. Albania would remain a part of the Ottoman Empire as the provinces of Scutari, Monastir and Janina until 1912.

Rise of Nations

By the 1870s, the Sublime Porte's reforms aimed at checking the Ottoman Empire's disintegration had clearly failed. The image of the "Turkish yoke" had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the empire's Balkan peoples, and their march toward independence quickened. The Albanians, because of the higher degree of Islamic influence, their internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian-populated lands to the emerging Balkan states--Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece—were the last of the Balkan peoples to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[41]

However, in the 19th century after the fall of the Albanian pashaliks and the Massacre of the Albanian Beys an Albanian National Awakening took place and many revolts against the Ottoman Empire were organized. Such revolts included the Albanian Revolts of 1833-1839, the Revolt of 1843–44, and the Revolt of 1847. A culmination of the Albanian National Awakening were the League of Prizren and the League of Peja, but they were unsuccessful to an Albanian independence, which occurred only in 1912, through the Albanian Declaration of Independence.

The Greek Revolution

As the Ottoman Empire began to weaken, uprising in the region of Rumelia lead to The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), also commonly known as the Greek Revolution. After a long and bloody struggle, and with the aid of the Great Powers, independence was finally granted by the Treaty of Constantinople in July 1832. Central to the Greek Revolution were the Arvanite and the Albanian Cam tribe of the Suliotes. A major contributor of the Greek Revolution was the Albanian ruler of Epirus, Ali Pasha Tepelena.

National Awakening

The borders set by the League of Prizren (Click to Enlarge)

The borders set by the League of Prizren (Click to Enlarge)

In response to the Serbian invasion of Albanian lands in the Villayete of Kosovo in the late 1800's, the Albanian beys (lords) united in the city of Prizren against the Serbian occupation. They soon gain support from all Albanian Villayets as Greece and Montenegro also started a bloody compain for the Albanian territories. The Sublime Porte, fearing that it would lose its grip on the western Balkans, initially supported the Albanian resistance against the newly formed Kingdoms of Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria. Ottomans cancelled their support when the League, under the influence of Abdyl bey Frashëri, became focused on working toward Albanian autonomy and requested merging of four Ottoman vilayets (Kosovo, Scutari,Monastir and Ioannina) into a new vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (the Albanian Vilayet). The League used military force to prevent the annexing areas of Plav and Gusinje assigned to Montenegro by the Congress of Berlin. After several battles with Montenegrin troops, the league was defeated by the Ottoman army sent by the Sultan.[40] The Albanian uprising of 1912, the Ottoman defeat in the Balkan Wars and the advance of Montenegrin, Serbian and Greek forces into territories claimed as Albanian, led to the proclamation of independence by Ismail Qemali in Vlora, on 28 November 1912.

Declaration of Independence

At All-Albanian Congress in Vlorë on 28 November 1912[41] Congress participants constituted the Assembly of Vlorë.[42] The assembly of eighty-three leaders meeting in Vlorë in November 1912 declared Albania an independent country and set up a provisional government. The complete text of the declaration[43] was:

In Vlora, on the 15th/28th of November. The President of Albania was Ismail Kemal Bey, who spoke of the great perils facing Albania today, the delegates have all decided unanimously that Albania, as of today, should be on her own, free and independent.

The Provisional Government of Albania was established on the second session of the assembly held on 4 December 1912. It was a government of ten members, led by Ismail Qemali until his resignation on 22 January 1914.[44] The Assembly also established the Senate (Albanian: Pleqësi) with an advisory role to the government, consisting of 18 members of the Assembly.[45]

In Vlora, on the 15th/28th of November. The President of Albania was Ismail Kemal Bey, who spoke of the great perils facing Albania today, the delegates have all decided unanimously that Albania, as of today, should be on her own, free and independent.

The Provisional Government of Albania was established on the second session of the assembly held on 4 December 1912. It was a government of ten members, led by Ismail Qemali until his resignation on 22 January 1914.[44] The Assembly also established the Senate (Albanian: Pleqësi) with an advisory role to the government, consisting of 18 members of the Assembly.[45]

Albania's independence was recognized by the Conference of London on 29 July 1913, but the drawing of the borders of the newly established Principality of Albania ignored the demographic realities of the time given Albanian territories to the neighboring countries, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia. As a result 3/4th of the Albanian territories with 80% Albanian majority where left out. The International Commission of Control was established on 15 October 1913 to take care of the administration of newly established Albania until its own political institutions were in order.[46] Its headquarters were in Vlorë.[47] The International Gendarmerie was established as the first law enforcement agency of the Principality of Albania. At the beginning of November the first gendarmerie members arrived in Albania. Wilhelm of Wied was selected as the first prince.[48]

The Balkan Wars

"Flee from me you blood sucking beasts", Albanian cartoon depicting Albania being pulled apart from Greece, Serbia and Montenegro

"Flee from me you blood sucking beasts", Albanian cartoon depicting Albania being pulled apart from Greece, Serbia and Montenegro

The First Balkan War (Albanian: Lufta Ballkanike, Bulgarian: Балканска война, Greek: Α΄ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος, Serbian: Први балкански рат Prvi Balkanski rat, Turkish: Birinci Balkan Savaşı), which lasted from October 1912 to May 1913, comprised actions of the Christian Balkan league (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria) against the Ottoman Empire. The combined armies of the Balkan states overcame the numerically inferior and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies and achieved rapid success.

As a result of the war, the allies captured and partitioned almost all remaining European territories of the Ottoman Empire. Being that the independence of Albania died with the League of Prizren, the region was still under Ottoman rule and it became a main target for the Christian Balkan League as they each manifestied their bloody expansion onto Albanian lands.

The Serb army first entered Ottoman territory inhabited by ethnic Albanians in October 1912 as part of its campaign in the then-ongoing First Balkan War.[7] The Kingdom of Serbia occupied most of the Albanian-inhabited lands including Albania's Adriatic coast. Serbian Gen. Božidar Janković was the Commander of the Serbian Third Army during the military campaign in Albania. The Serbian army met with strong Albanian guerrilla resistance, led by Isa Boletini, Azem Galica and other military leaders. During the Serbian occupation, Gen. Jankovic forced notables and local tribal leaders to sign a declaration of gratitude to King Petar I Karađorđević for their "liberation by the Serbian army".[8]

The army of the Kingdom of Serbia captured Durrës on 29 November 1912 without any resistance. Right after their arrival in Durrës, on 29 November 1912, the Kingdom of Serbia established Drač County, its district offices and appointed the governor of the county, mayor of the city and commander of the military garrison.[9]

During the occupation, the Serbian army committed numerous crimes against the Albanian population "with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of these regions."[5] The Serbian government denied reports of war crimes.[8]

Following the signing of the Treaty of London in May 1913 which awarded new lands to Serbia, including most of the former Vilayet of Kosovo, the Serbian government agreed to withdraw its troops from outside of its newly expanded territory. This allowed an Albanian state to exist peacefully. The final withdrawal of Serb personnel from Albania was in October 1913.

Shkodër and its surrounding had long been desired by Montenegro, although its inhabitants were overwhelmingly ethnic Albanians. The Siege of Scutari took place on 23 April 1913 between the allied forces of Montenegro and Serbia against the forces of the Ottoman Empire and the Provisional Government of Albania.

Montenegro took Shkodër on 23 April 1913, but when the war was over the Great Powers didn't give the city to the Kingdom of Montenegro, which was compelled to evacuate it in May 1913, in accordance with the London Conference of Ambassadors. The army's withdrawal was hastened by a small naval flotilla of British and Italian gunboats that moved up the Bojana River and across the Adriatic coastline.[10]

The Greek Army controlled territory that would be later incorporated into the Albanian state before the declaration of Albanian Independence in Vlorë. On 18 November 1912, after a successful uprising and 10 days prior to the Albanian Declaration of Independence, local Maj. Spyros Spyromilios expelled the Ottomans from the Himara region.[11] The Greek Navy also shelled the city of Vlora on 3 December 1912.[12][13] The Greek Army didn't capture Vlore, which was of great interest to Italy.[14]

Greek forces were stationed in what would become southern Albania until March 1914. After the Great Powers agreed on the terms of the Protocol of Florence in December 1913, Greece was forced to retreat from the towns of Korçë, Gjirokastër and Sarandë and the surrounding territories.[15]

Under strong international pressure, Albania's Balkan neighbors were forced to withdraw from the territory of the internationally recognized state of Albania in 1913. The new Principality of Albania included only about half of the ethnic Albanian population, while a large number of Albanians remained in neighboring countries.[16]

As a result of the war, the allies captured and partitioned almost all remaining European territories of the Ottoman Empire. Being that the independence of Albania died with the League of Prizren, the region was still under Ottoman rule and it became a main target for the Christian Balkan League as they each manifestied their bloody expansion onto Albanian lands.

The Serb army first entered Ottoman territory inhabited by ethnic Albanians in October 1912 as part of its campaign in the then-ongoing First Balkan War.[7] The Kingdom of Serbia occupied most of the Albanian-inhabited lands including Albania's Adriatic coast. Serbian Gen. Božidar Janković was the Commander of the Serbian Third Army during the military campaign in Albania. The Serbian army met with strong Albanian guerrilla resistance, led by Isa Boletini, Azem Galica and other military leaders. During the Serbian occupation, Gen. Jankovic forced notables and local tribal leaders to sign a declaration of gratitude to King Petar I Karađorđević for their "liberation by the Serbian army".[8]

The army of the Kingdom of Serbia captured Durrës on 29 November 1912 without any resistance. Right after their arrival in Durrës, on 29 November 1912, the Kingdom of Serbia established Drač County, its district offices and appointed the governor of the county, mayor of the city and commander of the military garrison.[9]

During the occupation, the Serbian army committed numerous crimes against the Albanian population "with a view to the entire transformation of the ethnic character of these regions."[5] The Serbian government denied reports of war crimes.[8]

Following the signing of the Treaty of London in May 1913 which awarded new lands to Serbia, including most of the former Vilayet of Kosovo, the Serbian government agreed to withdraw its troops from outside of its newly expanded territory. This allowed an Albanian state to exist peacefully. The final withdrawal of Serb personnel from Albania was in October 1913.

Shkodër and its surrounding had long been desired by Montenegro, although its inhabitants were overwhelmingly ethnic Albanians. The Siege of Scutari took place on 23 April 1913 between the allied forces of Montenegro and Serbia against the forces of the Ottoman Empire and the Provisional Government of Albania.

Montenegro took Shkodër on 23 April 1913, but when the war was over the Great Powers didn't give the city to the Kingdom of Montenegro, which was compelled to evacuate it in May 1913, in accordance with the London Conference of Ambassadors. The army's withdrawal was hastened by a small naval flotilla of British and Italian gunboats that moved up the Bojana River and across the Adriatic coastline.[10]

The Greek Army controlled territory that would be later incorporated into the Albanian state before the declaration of Albanian Independence in Vlorë. On 18 November 1912, after a successful uprising and 10 days prior to the Albanian Declaration of Independence, local Maj. Spyros Spyromilios expelled the Ottomans from the Himara region.[11] The Greek Navy also shelled the city of Vlora on 3 December 1912.[12][13] The Greek Army didn't capture Vlore, which was of great interest to Italy.[14]

Greek forces were stationed in what would become southern Albania until March 1914. After the Great Powers agreed on the terms of the Protocol of Florence in December 1913, Greece was forced to retreat from the towns of Korçë, Gjirokastër and Sarandë and the surrounding territories.[15]

Under strong international pressure, Albania's Balkan neighbors were forced to withdraw from the territory of the internationally recognized state of Albania in 1913. The new Principality of Albania included only about half of the ethnic Albanian population, while a large number of Albanians remained in neighboring countries.[16]

The Splitting

Under the secret Treaty of London signed in April 1915, Triple Entente powers promised Italy that it would gain Vlorë and nearby lands and a protectorate over Albania in exchange for entering the war against Austria-Hungary. Serbia and Montenegro were promised much of northern Albania, and Greece was promised much of the country's southern half. The treaty was to leave a tiny Albanian state that would be represented by Italy in its relations with the other major powers, thus basically would have no foreign policy. In September 1918, the Entente forces broke through the Central Powers' lines north of Thessaloniki, and within days Austro-Hungarian forces began to withdraw from Albania. When the war ended on November 11, 1918, Italy's army had occupied most of Albania, Serbia held much of the country's northern mountains, Greece occupied a sliver of land within Albania's 1913 borders; and French forces occupied Korçë and Shkodër as well as other regions with sizable Albanian populations such as Kosovo, which was returned to Serbia.

The Principality of Albania

Prince Weid

Prince Weid

In supporting the independence of Albania, the Great Powers were assisted by Aubrey Herbert, a British MP who passionately advocated the Albanian cause in London. As a result, Herbert was offered the crown of Albania, but was dissuaded by the British Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, from accepting. Instead the offer went to William of Wied, a German prince who accepted and became sovereign of the new Principality of Albania.[48]

The Principality was established on 21 February 1914. The Great Powers selected Prince William of Wied, a nephew of Queen Elisabeth of Romania to become the sovereign of the newly independent Albania. A formal offer was made by 18 Albanian delegates representing the 18 districts of Albania on 21 February 1914, an offer which he accepted. Outside of Albania William was styled prince, but in Albania he was referred to as Mbret (King) so as not to seem inferior to the King of Montenegro.

Prince William arrived in Albania at his provisional capital of Durrës on 7 March 1914 along with the Royal family. The security of Albania was to be provided by a Gendarmerie commanded by Dutch officers.

The Principality was established on 21 February 1914. The Great Powers selected Prince William of Wied, a nephew of Queen Elisabeth of Romania to become the sovereign of the newly independent Albania. A formal offer was made by 18 Albanian delegates representing the 18 districts of Albania on 21 February 1914, an offer which he accepted. Outside of Albania William was styled prince, but in Albania he was referred to as Mbret (King) so as not to seem inferior to the King of Montenegro.

Prince William arrived in Albania at his provisional capital of Durrës on 7 March 1914 along with the Royal family. The security of Albania was to be provided by a Gendarmerie commanded by Dutch officers.

World War I

Being unsatisfied by the support that Austro-Hungary showed towards protecting the integrity of the Albanian borders,thus losing Durrës, their outing to the Adriatic coast and growing bitter that they were forced to remove troops from Albania, Serbia assassinates Prince Ferdinand of Austro-Hungary thus launching the first World War. World War I interrupted all government activities in Albania, and the country was split into a number of regional governments. Political chaos engulfed Albania after the outbreak of World War I. Surrounded by insurgents in Durrës, Prince William departed the country in September 1914, just six months after arriving, and subsequently joined the German army and served on the Eastern Front. The Albanian people split along religious and tribal lines after the prince's departure. Muslims demanded a Muslim prince and looked to Turkey as the protector of the privileges they had enjoyed, hence many beys and clan chiefs, recognized no superior authority. In late October 1914, Greek forces entered Albania in the Protocol of Corfu's recognized Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus. Italy occupied Vlorë, and Serbia and Montenegro occupied parts of northern Albania until a Central Powers offensive scattered the Serbian army, which was evacuated by the French to Thessaloniki. Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian forces then occupied about two-thirds of the country

The Albanian Monarchy

King of Albanians, King Zog I, Skanderbeg III

King of Albanians, King Zog I, Skanderbeg III

The short-lived monarchy (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928), to be replaced by another monarchy of King Zog I (1928–1939) who intended to create a democratic and European government. Because of the territorial claims from the neighboring countries, the Albanian Monarchy sought the support of the closest European neighbor, Italy. Striving to keep its eyes in the west, the kingdom was supported by the fascist regime in Italy and the two countries maintained close relations until Italy's sudden invasion of the country in 1939. Albania was occupied by Fascist Italy and then by Nazi Germany during World War II.

World War II

After being militarily occupied by Italy, from 1939 until 1943 the Albanian Kingdom was a protectorate and a dependency of Italy governed by the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and his government. After the Axis' invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, territories of Yugoslavia with substantial Albanian population were annexed to Albania: most of Kosovo[a] as well as Western Macedonia, the town of Tutin in Central Serbia and a strip of Eastern Montenegro.[56] After the capitulation of Italy in 1943, Nazi Germany occupied Albania too. The nationalist Balli Kombetar, which had fought against Italy, formed a "neutral" government in Tirana, and side by side with the Germans fought against the communist-led National Liberation Movement of Albania[57]

Genocide of the Albanian Chams

The Cham issue started with the invasion of southern Epirus by Greece even before the start of the first Balkan war. The first recorded massacres happen in 1913 in Paramythia leaving about 500 Cham Albanians massacred by Greek forces. expulsion of Cham Albanians from Greece was a forced emigration of thousands of Cham Albanians after the Second World War to Albania, by the Resistance National Republican Greek League (EDES) forces. The EDES and the Joint Allied Military Mission in the Axis-occupied Greece accused the Chams for collaborating with the German Nazis and Italian Fascists during the war. The Cham community had suffered horrendous crimes, discrimination since the beginning of Balkans Wars. They lost their struggle for liberation after the Greek invasion of Chameria which later lead to Greece's annexation of southern Epirus in 1913. After the annexation, the Greek government followed a forced assimilation and expulsion policy against the Cham population. While it is possible that some Chams collaborated with the Axis powers under the promise of liberation, others enlisted in the resistance forces of the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) forming the Ali Demi Battalion and Chameria Battalion, fighting along side the Greek resistance and the Albanian Liberation Front (LANÇ). Greeks in opposition however, collaborated in large numbers with the Axis powers. A prime example was the Security Battalion, derisively known as Germanotsoliades or Tagmatasfalites were Greek collaborationist military groups, formed during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II in order to support the German occupation troops.

Various sources put the death toll between 200-300.[1] The estimated amount of Albanians expelled from Chameria to Albania and Turkey varies: figures of 14,000, 19,000, 28,000 and 35,000 have been given.[2][3][4][5]

Various sources put the death toll between 200-300.[1] The estimated amount of Albanians expelled from Chameria to Albania and Turkey varies: figures of 14,000, 19,000, 28,000 and 35,000 have been given.[2][3][4][5]

Rise of Communism

By the end of World War II, the main military and political force of the country was the communist party. After the liberation of Albania from Nazi occupation, the country became a Communist state, the People's Republic of Albania (renamed "the People's Socialist Republic of Albania" in 1976), which was led by Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labour of Albania.